Chichimeca

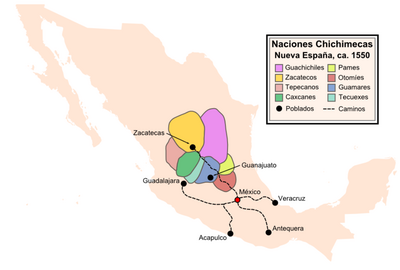

Chichimeca (Spanish: [tʃitʃiˈmeka] ) is the name that the Nahua peoples of Mexico generically applied to nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples who were established in present-day Bajío region of Mexico. Chichimeca carried the same meaning as the Roman term "barbarian" that described Germanic tribes. The name, with its pejorative sense, was adopted by the Spanish Empire. In the words of scholar Charlotte M. Gradie, "for the Spanish, the Chichimecas were a wild, nomadic people who lived north of the Valley of Mexico. They had no fixed dwelling places, lived by hunting, wore little clothes and fiercely resisted foreign intrusion into their territory, which happened to contain silver mines the Spanish wished to exploit."[1] Gradie noted that Chichimeca was used as a broad and generalizing term by outsiders, writing, "[it] was used by both Spanish and Nahuatl speakers to refer collectively to many different people who exhibited a wide range of cultural development from hunter-gatherers to sedentary agriculturalists with sophisticated political organizations."[2] They practiced animal sacrifice, and they were feared for their expertise and brutality in war.[3]

The Chichimeca War (1550-1590) ended with the Spanish making favorable peace terms with the Chichimeca. Spanish/Chichimeca interaction resulted in a "drastic population decline in population of all the peoples known collectively as Chichimecas, and to their eventual disappearance as peoples of all save the Pames of San Luis Potosí and the related Chichimeca-Jonaz of the Sierra Gorda in eastern Guanajuato."[4] In modern times, only one ethnic group is customarily referred to as Chichimecs, namely the Chichimeca Jonaz, a few thousand of whom live in the state of Guanajuato.

Etymology

[edit]The Nahuatl name Chīchīmēcah (plural, pronounced [tʃiːtʃiːˈmeːkaʔ]; singular Chīchīmēcatl) means "inhabitants of Chichiman," Chichiman meaning "area of milk." It is sometimes said to be related to chichi "dog", but both i's in chichi are short, and both in Chīchīmēcah are long. That changes the meaning, as vowel length is phonemic in Nahuatl.[5]

Ethnohistorical descriptions

[edit]In the late sixteenth century, Gonzalo de las Casas wrote about the Chichimec. He had received an encomienda near Durango and fought in the wars against the Chichimec peoples: the Pame, the Guachichil, the Guamare and the Zacateco, who lived in the area known at the time as "La Gran Chichimeca." Las Casas' account was called Report of the Chichimeca and the Justness of the War Against Them. He described the people, providing ethnographic information. He wrote that they only covered their genitalia with clothing; painted their bodies; and ate only game, roots and berries. He mentioned, in order to prove their supposed barbarity, that Chichimec women, having given birth, continued traveling on the same day without stopping to recover.[6]

In the late 16th century, according to the Spanish, the Chichimeca did not worship idols as did many of the surrounding indigenous peoples.[7]

Wars with the Spanish

[edit]Chichimeca military strikes against the Spanish included raidings, ambushing critical economic routes, and pillaging. In the long-running Chichimeca War (1550–1590), the Spanish initially attempted to defeat the combined Chichimeca peoples in a war of "fire and blood", but eventually sought peace as they were unable to defeat them. The Chichimeca's small-scale raids proved effective. To end the war, the Spanish adopted a "Purchase for Peace" program by providing foods, tools, livestock, and land to the Chichimecas, sending Spanish to teach them agriculture as a livelihood, and by converting them to Catholicism. Within a century, the Spanish and Chichimeca assimilated.[8]

References

[edit]De las Casas, Gonzalo. (1571). The War of the Chichimecas

- ^ Gradie, Charlotte M. "Discovering the Chichimecas" Academy of American Franciscan History, Vol 51, No. 1 (July 1994), p. 68

- ^ Gradie, Charlotte M. "Discovering the Chichimecas" Academy of American Franciscan History, Vol 51, No. 1 (July 1994), p. 68

- ^ Gradie, Charlotte M. "Chichimec." In Davíd Carrasco (ed).The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures. : Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780195188431

- ^ The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. 2: Mesoamerica, Part 2. Cambridge University Press. 2000. pp. 111–113. ISBN 9780521652049.

- ^ See Andrews 2003 (pp.496 and 507), Karttunen 1983 (p.48), and Lockhart 2001 (p.214)

- ^ As cited in Gradie (1994).

- ^ http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/aztecs/Chichimecas.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Powell, Phillip Wayne (1952), Soldiers, Indians & Silver, Berkeley: U of California Press, pp. 182-199; LatinoLA | Comunidad :: Indigenous Origins Archived 2019-01-04 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

[edit]- Andrews, J. Richard (2003). Introduction to Classical Nahuatl (Revised ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- De las Casas, Gonzalo (1571). The War of the Chichimecas.

- Gradie, Charlotte M. "Chichimec." In Davíd Carrasco (ed).The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures. : Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780195188431

- Gradie, Charlotte M. (1994). "Discovering the Chichimeca". Americas. 51 (1). The Americas, Vol. 51, No. 1: 67–88. doi:10.2307/1008356. JSTOR 1008356. S2CID 145002405.

- Karttunen, Frances (1983). An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Lockhart, James (2001). Nahuatl as Written. Stanford University Press.

- Lumholtz, Carl (1987) [1900]. Unknown Mexico, Explorations in the Sierra Madre and Other Regions, 1890-1898. 2 vols (reprint ed.). New York: Dover Publications.

- Powell, Philip Wayne (1969). Soldiers, Indians, & Silver: The Northward Advance of New Spain, 1550-1600. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Secretariá de Turismo del Estado de Zacatecas (2005). "Zonas Arqueológicas" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2005-12-07. Retrieved 2006-04-25.

- Smith, Michael E. (1984). "The Aztlan Migrations of Nahuatl Chronicles: Myth or History?" (PDF online facsimile). Ethnohistory. 31 (3). Columbus, OH: American Society for Ethnohistory: 153–186. doi:10.2307/482619. ISSN 0014-1801. JSTOR 482619. OCLC 145142543.