Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright | |

|---|---|

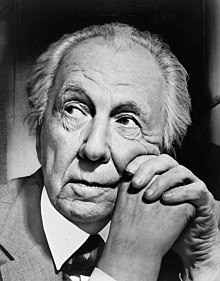

Wright in 1954 | |

| Born | June 8, 1867 |

| Died | April 9, 1959 (aged 91) Phoenix, Arizona, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Wisconsin–Madison |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouses |

|

| Partner | Mamah Borthwick (1909–1914) |

| Children | 8, including Lloyd Wright and John Lloyd Wright |

| Awards | |

| Buildings |

|

| Projects | |

| Signature | |

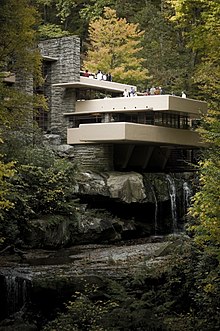

Frank Lloyd Wright Sr. (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key role in the architectural movements of the twentieth century, influencing architects worldwide through his works and mentoring hundreds of apprentices in his Taliesin Fellowship.[1][2] Wright believed in designing in harmony with humanity and the environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was exemplified in Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".[3]

Wright was a pioneer of what came to be called the Prairie School movement of architecture and also developed the concept of the Usonian home in Broadacre City, his vision for urban planning in the United States. He also designed original and innovative offices, churches, schools, skyscrapers, hotels, museums, and other commercial projects. Wright-designed interior elements (including leaded glass windows, floors, furniture and even tableware) were integrated into these structures. He wrote several books and numerous articles and was a popular lecturer in the United States and in Europe. Wright was recognized in 1991 by the American Institute of Architects as "the greatest American architect of all time".[3] In 2019, a selection of his work became a listed World Heritage Site as The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Raised in rural Wisconsin, Wright studied civil engineering at the University of Wisconsin and then apprenticed in Chicago, briefly with Joseph Lyman Silsbee, and then with Louis Sullivan at Adler & Sullivan. Wright opened his own successful Chicago practice in 1893 and established a studio in his Oak Park, Illinois home in 1898. His fame increased and his personal life sometimes made headlines: leaving his first wife Catherine "Kitty" Tobin for Mamah Cheney in 1909; the murder of Mamah and her children and others at his Taliesin estate by a staff member in 1914; his tempestuous marriage with second wife Miriam Noel (m. 1923–1927); and his courtship and marriage with Olgivanna Lazović (m. 1928–1959).

Early life and education

[edit]Childhood (1867–1885)

[edit]Wright was born on June 8, 1867, in the town of Richland Center, Wisconsin, but maintained throughout his life that he was born in 1869.[4][5] In 1987 a biographer of Wright suggested that he had been christened as "Frank Lincoln Wright" or "Franklin Lincoln Wright" but these assertions were not supported by any documentation.[6]

Wright's father, William Cary Wright (1825–1904), was a "gifted musician, orator, and sometime preacher who had been admitted to the bar in 1857."[7] He was also a published composer.[8] Originally from Massachusetts, William Wright had been a Baptist minister, but he later joined his wife's family in the Unitarian faith.

Wright's mother, Anna Lloyd Jones (1838/39–1923) was a teacher and a member of the Lloyd Jones clan; her parents had emigrated from Wales to Wisconsin.[9] One of Anna's brothers was Jenkin Lloyd Jones, an important figure in the spread of the Unitarian faith in the Midwest.

According to Wright's autobiography, his mother declared when she was expecting that her first child would grow up to build beautiful buildings. She decorated his nursery with engravings of English cathedrals torn from a periodical to encourage the infant's ambition.[10]

Wright grew up in an "unstable household, [...] constant lack of resources, [...] unrelieved poverty and anxiety" and had a "deeply disturbed and obviously unhappy childhood".[11] His father held pastorates in McGregor, Iowa (1869), Pawtucket, Rhode Island (1871), and Weymouth, Massachusetts (1874). Because the Wright family struggled financially also in Weymouth, they returned to Spring Green, where the supportive Lloyd Jones family could help William find employment. In 1877, they settled in Madison, where William gave music lessons and served as the secretary to the newly formed Unitarian society. Although William was a distant parent, he shared his love of music with his children.[11]

In 1876, Anna saw an exhibit of educational blocks called the Froebel Gifts, the foundation of an innovative kindergarten curriculum. Anna, a trained teacher, was excited by the program and bought a set with which the 9-year old Wright spent much time playing. The blocks in the set were geometrically shaped and could be assembled in various combinations to form two- and three-dimensional compositions. In his autobiography, Wright described the influence of these exercises on his approach to design: "For several years, I sat at the little kindergarten table-top... and played... with the cube, the sphere and the triangle – these smooth wooden maple blocks... All are in my fingers to this day... "[12]

In 1881, soon after Wright turned 14, his parents separated. In 1884, his father sued for a divorce from Anna on the grounds of "... emotional cruelty and physical violence and spousal abandonment".[13] Wright attended Madison High School, but there is no evidence that he graduated.[14] His father left Wisconsin after the divorce was granted in 1885. Wright said that he never saw his father again.[15]

Education (1885–1887)

[edit]In 1886, at age 19, Wright was admitted to the University of Wisconsin–Madison as a special student. He worked under Allan D. Conover,[16] a professor of civil engineering, before leaving the school without taking a degree;[17] in 1955, the university presented Wright, then 88 years old, with an honorary doctorate of fine arts.[18]

Wright's uncle Jenkin Lloyd Jones had commissioned the Chicago architectural firm of Joseph Lyman Silsbee to design the All Souls Church in Chicago in 1885. In 1886, the Silsbee firm was commissioned by Jones to design the Unity Chapel as his private family chapel in Wyoming, Wisconsin.

Although not officially employed by Silsbee, Wright was an accomplished draftsman and "looked after the interior [drawings and construction]" in Wisconsin.[19] This chapel is thus Wright's earliest known work.[20]

After the chapel was finished, Wright moved to Chicago.[20]

Early career

[edit]Silsbee and other early work experience (1887–1888)

[edit]In 1887, Wright arrived in Chicago in search of employment. As a result of the devastating Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and a population boom, new development was plentiful. Wright later recorded in his autobiography that his first impression of Chicago was as an ugly and chaotic city.[21] Within days of his arrival, and after interviews with several prominent firms, he was hired as a draftsman with Joseph Lyman Silsbee.[22] While with the firm, he also worked on two other family projects: All Souls Church in Chicago for his uncle, Jenkin Lloyd Jones, and the Hillside Home School I in Spring Green for two of his aunts.[23] Others working in Silsbee's office at the time included Cecil S. Corwin (1860–1941), George W. Maher (1864–1926), and George G. Elmslie (1869–1952). Corwin, who was seven years older than Wright, soon took his young colleague under his wing and the two became close friends.

Feeling underpaid and looking to earn more, Wright briefly left Silsbee to work for architect William W. Clay (1849–1926).[24] However, Wright soon felt overwhelmed by his new level of responsibility and returned to Silsbee, but this time with a raise in salary.[25] Although Silsbee adhered mainly to Victorian and Revivalist architecture, Wright found his work to be more "gracefully picturesque" than the other "brutalities" of the period.[26] Wright remained with Silsbee for a little less than a year, leaving to work for Adler & Sullivan around November 1887.

Adler & Sullivan (1888–1893)

[edit]

Wright learned that the Chicago firm of Adler & Sullivan was "... looking for someone to make the finished drawings for the interior of the Auditorium Building".[27] Wright demonstrated that he was a competent impressionist of Louis Sullivan's ornamental designs and two short interviews later, was an official apprentice in the firm.[28] Wright did not get along well with Sullivan's other draftsmen; he wrote that several violent altercations occurred between them during the first years of his apprenticeship. For that matter, Sullivan showed very little respect for his own employees as well.[29] In spite of this, "Sullivan took [Wright] under his wing and gave him great design responsibility."[30] As an act of respect, Wright would later refer to Sullivan as lieber Meister (German for "dear master").[30] He also formed a bond with office foreman Paul Mueller. Wright later engaged Mueller in the construction of several of his public and commercial buildings between 1903 and 1923.[31]

By 1890, Wright had an office next to Sullivan's that he shared with friend and draftsman George Elmslie, who had been hired by Sullivan at Wright's request.[31][32] Wright had risen to head draftsman and handled all residential design work in the office. As a general rule, the firm of Adler & Sullivan did not design or build houses, but would oblige when asked by the clients of their important commercial projects.[citation needed] Wright was occupied by the firm's major commissions during office hours, so house designs were relegated to evening and weekend overtime hours at his home studio. He later claimed total responsibility for the design of these houses, but a careful inspection of their architectural style (and accounts from historian Robert Twombly) suggests that Sullivan dictated the overall form and motifs of the residential works; Wright's design duties were often reduced to detailing the projects from Sullivan's sketches.[32] During this time, Wright was assigned to work on the Sullivan's bungalow (1890) and the James A. Charnley bungalow (1890) in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, the Berry-MacHarg House,[33] James A. Charnley House (both 1891), and the Albert Sullivan House (1892), all in Chicago.[34][35]

Despite Sullivan's loan and overtime salary, Wright was constantly short on funds. Wright admitted that his poor finances were likely due to his expensive tastes in wardrobe and vehicles, and the extra luxuries he designed into his house.[36] To supplement his income and repay his debts, Wright accepted independent commissions for at least nine houses. These "bootlegged" houses, as he later called them, were conservatively designed in variations of the fashionable Queen Anne and Colonial Revival styles. Nevertheless, unlike the prevailing architecture of the period, each house emphasized simple geometric massing and contained features such as bands of horizontal windows, occasional cantilevers, and open floor plans, which would become hallmarks of his later work. Eight of these early houses remain today, including the Thomas Gale, Robert Parker, George Blossom, and Walter Gale houses.[37]

As with the residential projects for Adler & Sullivan, he designed his bootleg houses on his own time. Sullivan knew nothing of the independent works until 1893, when he recognized that one of the houses was unmistakably a Frank Lloyd Wright design.[38] This particular house, built for Allison Harlan, was only blocks away from Sullivan's townhouse in the Chicago community of Kenwood.[39] Aside from the location, the geometric purity of the composition and balcony tracery in the same style as the Charnley House likely gave away Wright's involvement.[40] Since Wright's five-year contract forbade any outside work, the incident led to his departure from Sullivan's firm.[35] Several stories recount the break in the relationship between Sullivan and Wright; even Wright later told two different versions of the occurrence. In An Autobiography, Wright claimed that he was unaware that his side ventures were a breach of his contract. When Sullivan learned of them, he was angered and offended; he prohibited any further outside commissions and refused to issue Wright the deed to his Oak Park house until after he completed his five years. Wright could not bear the new hostility from his master and thought that the situation was unjust. He "... threw down [his] pencil and walked out of the Adler & Sullivan office never to return". Dankmar Adler, who was more sympathetic to Wright's actions, later sent him the deed.[41] However, Wright told his Taliesin apprentices (as recorded by Edgar Tafel) that Sullivan fired him on the spot upon learning of the Harlan House. Tafel also recounted that Wright had Cecil Corwin sign several of the bootleg jobs, indicating that Wright was aware of their forbidden nature. Regardless of the correct series of events, Wright and Sullivan did not meet or speak for 12 years.[35][42]

Transition and experimentation (1893–1900)

[edit]

After leaving Adler & Sullivan, Wright established his own practice on the top floor of the Sullivan-designed Schiller Building on Randolph Street in Chicago. Wright chose to locate his office in the building because the tower location reminded him of the office of Adler & Sullivan. Cecil Corwin followed Wright and set up his architecture practice in the same office, but the two worked independently and did not consider themselves partners.

In 1896, Wright moved from the Schiller Building to the nearby and newly completed Steinway Hall building. The loft space was shared with Robert C. Spencer Jr., Myron Hunt, and Dwight H. Perkins.[43] These young architects, inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement and the philosophies of Louis Sullivan, formed what became known as the Prairie School.[44] They were joined by Perkins' apprentice Marion Mahony, who in 1895 transferred to Wright's team of drafters and took over production of his presentation drawings and watercolor renderings. Mahony, the third woman to be licensed as an architect in Illinois and one of the first licensed female architects in the U.S., also designed furniture, leaded glass windows, and light fixtures, among other features, for Wright's houses. Between 1894 and the early 1910s, several other leading Prairie School architects and many of Wright's future employees launched their careers in the offices of Steinway Hall.[45][46]

Wright's projects during this period followed two basic models. His first independent commission, the Winslow House, combined Sullivanesque ornamentation with the emphasis on simple geometry and horizontal lines. The Francis Apartments (1895, demolished 1971), Heller House (1896), Rollin Furbeck House (1897) and Husser House (1899, demolished 1926) were designed in the same mode. For his more conservative clients, Wright designed more traditional dwellings. These included the Dutch Colonial Revival style Bagley House (1894), Tudor Revival style Moore House I (1895), and Queen Anne style Charles E. Roberts House (1896).[47] While Wright could not afford to turn down clients over disagreements in taste, even his most conservative designs retained simplified massing and occasional Sullivan-inspired details.[48]

Soon after the completion of the Winslow House in 1894, Edward Waller, a friend and former client, invited Wright to meet Chicago architect and planner Daniel Burnham. Burnham had been impressed by the Winslow House and other examples of Wright's work; he offered to finance a four-year education at the École des Beaux-Arts and two years in Rome. To top it off, Wright would have a position in Burnham's firm upon his return. In spite of guaranteed success and support of his family, Wright declined the offer. Burnham, who had directed the classical design of the World's Columbian Exposition and was a major proponent of the Beaux Arts movement, thought that Wright was making a foolish mistake.[49][50] Yet for Wright, the classical education of the École lacked creativity and was altogether at odds with his vision of modern American architecture.[51][52]

Wright relocated his practice to his home in 1898 to bring his work and family lives closer. This move made further sense as the majority of the architect's projects at that time were in Oak Park or neighboring River Forest. The birth of three more children prompted Wright to sacrifice his original home studio space for additional bedrooms and necessitated his design and construction of an expansive studio addition to the north of the main house. The space, which included a hanging balcony within the two-story drafting room, was one of Wright's first experiments with innovative structure. The studio embodied Wright's developing aesthetics and would become the laboratory from which his next 10 years of architectural creations would emerge.[53]

Prairie Style houses (1900–1914)

[edit]

By 1901, Wright had completed about 50 projects, including many houses in Oak Park. As his son John Lloyd Wright wrote:[54]

William Eugene Drummond, Francis Barry Byrne, Walter Burley Griffin, Albert Chase McArthur, Marion Mahony, Isabel Roberts, and George Willis were the draftsmen. Five men, two women. They wore flowing ties, and smocks suitable to the realm. The men wore their hair like Papa, all except Albert, he didn't have enough hair. They worshiped Papa! Papa liked them! I know that each one of them was then making valuable contributions to the pioneering of the modern American architecture for which my father gets the full glory, headaches, and recognition today!

Between 1900 and 1901, Frank Lloyd Wright completed four houses, which have since been identified as the onset of the "Prairie Style". Two, the Hickox and Bradley Houses, were the last transitional step between Wright's early designs and the Prairie creations.[55] Meanwhile, the Thomas House and Willits House received recognition as the first mature examples of the new style.[56][57] At the same time, Wright gave his new ideas for the American house widespread awareness through two publications in the Ladies' Home Journal. The articles were in response to an invitation from the president of Curtis Publishing Company, Edward Bok, as part of a project to improve modern house design.[citation needed] "A Home in a Prairie Town" and "A Small House with Lots of Room in it" appeared respectively in the February and July 1901 issues of the journal. Although neither of the affordable house plans was ever constructed, Wright received increased requests for similar designs in following years.[55] Wright came to Buffalo and designed homes for three of the company's executives: the Darwin D. Martin House (1904), the William R. Heath House 1905), and the Walter V. Davidson House (1908). Wright also designed Graycliff (1931), a summer home for the Martin family on the shore of Lake Erie. Other Wright houses considered to be masterpieces of the Prairie Style are the Frederick Robie House in Chicago and the Avery and Queene Coonley House in Riverside, Illinois. The Robie House, with its extended cantilevered roof lines supported by a 110-foot-long (34 m) channel of steel, is the most dramatic. Its living and dining areas form virtually one uninterrupted space. With this and other buildings, included in the publication of the Wasmuth Portfolio (1910), Wright's work became known to European architects and had a profound influence on them after World War I.

Wright's residential designs of this era were known as "prairie houses" because the designs complemented the land around Chicago.[58] Prairie Style houses often have a combination of these features: one or two stories with one-story projections, an open floor plan, low-pitched roofs with broad, overhanging eaves, strong horizontal lines, ribbons of windows (often casements), a prominent central chimney, built-in stylized cabinetry, and a wide use of natural materials – especially stone and wood.[59]

By 1909, Wright had begun to reject the upper-middle-class Prairie Style single-family house model, shifting his focus to a more democratic architecture.[60] Wright went to Europe in 1909 with a portfolio of his work and presented it to Berlin publisher Ernst Wasmuth.[61] Studies and Executed Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, published in 1911, was the first major exposure of Wright's work in Europe. The work contained more than 100 lithographs of Wright's designs and is commonly known as the Wasmuth Portfolio.[62]

Notable public works (1900–1917)

[edit]

Wright designed the house of Cornell University's chapter of Alpha Delta Phi literary society (1900), the Hillside Home School II (built for his aunts) in Spring Green, Wisconsin (1901) and the Unity Temple (1905) in Oak Park, Illinois.[63][64] As a lifelong Unitarian and member of Unity Temple, Wright offered his services to the congregation after their church burned down, working on the building from 1905 to 1909. Wright later said that Unity Temple was the edifice in which he ceased to be an architect of structure, and became an architect of space.[65]

Some other early notable public buildings and projects in this era: the Larkin Administration Building (1905); the Geneva Inn (Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, 1911); the Midway Gardens (Chicago, Illinois, 1913); the Banff National Park Pavilion (Alberta, Canada, 1914).

Designing in Japan (1917–1922)

[edit]

While working in Japan, Wright left an impressive architectural heritage. The Imperial Hotel, completed in 1923, is the most important.[66] Thanks to its solid foundations and steel construction, the hotel survived the Great Kantō Earthquake almost unscathed.[67] The hotel was damaged during the bombing of Tokyo and by the subsequent US military occupation of it after World War II.[68] As land in the center of Tokyo increased in value the hotel was deemed obsolete and was demolished in 1968, but the lobby was saved and later re-constructed at the Meiji Mura architecture museum in Nagoya in 1976.[69]

Jiyu Gakuen was founded as a girls' school in 1921. The construction of the main building began in 1921 under Wright's direction and, after his departure, was continued by Endo.[70] The school building, like the Imperial Hotel, is covered with Ōya stones.[71][72]

The Yodoko Guesthouse (designed in 1918 and completed in 1924) was built as the summer villa for Tadzaemon Yamamura.

Frank Lloyd Wright's architecture had a strong influence on young Japanese architects. The Japanese architects Wright commissioned to carry out his designs were Arata Endo, Takehiko Okami, Taue Sasaki and Kameshiro Tsuchiura. Endo supervised the completion of the Imperial Hotel after Wright's departure in 1922 and also supervised the construction of the Jiyu Gakuen Girls' School and the Yodokō Guest House. Tsuchiura went on to create so-called "light" buildings, which had similarities to Wright's later work.[73]

Textile concrete block system

[edit]

In the early 1920s, Wright designed a "textile" concrete block system. The system of precast blocks, reinforced by an internal system of bars, enabled "fabrication as infinite in color, texture, and variety as in that rug."[74] Wright first used his textile block system on the Millard House in Pasadena, California, in 1923. Typically Wrightian is the joining of the structure to its site by a series of terraces that reach out into and reorder the landscape, making it an integral part of the architect's vision.[75] With the Ennis House and the Samuel Freeman House (both 1923), Wright had further opportunities to test the limits of the textile block system, including limited use in the Arizona Biltmore Hotel in 1927.[76] The Ennis house is often used in films, television, and print media to represent the future.[75] Wright's son, Lloyd Wright, supervised construction for the Storer, Freeman, and Ennis Houses. Architectural historian Thomas Hines has suggested that Lloyd's contribution to these projects is often overlooked.[77]

After World War II, Wright updated the concrete block system, calling it the Usonian Automatic system, resulting in the construction of several notable homes. As he explained in The Natural House (1954), "The original blocks are made on the site by ramming concrete into wood or metal wrap-around forms, with one outside face (which may be patterned), and one rear or inside face, generally coffered, for lightness."[74]

Midlife problems

[edit]Family turmoil

[edit]

In 1903, while Wright was designing a house for Edwin Cheney (a neighbor in Oak Park), he became enamored with Cheney's wife, Mamah Borthwick Cheney. Mamah was a modern woman with interests outside the home. She was an early feminist, and Wright viewed her as his intellectual equal. Their relationship became the talk of the town; they often could be seen taking rides in Wright's automobile through Oak Park.[citation needed] In 1909, Wright and Mamah Cheney met up in Europe, leaving their spouses and children behind. Wright remained in Europe for almost a year, first in Florence, Italy (where he lived with his eldest son Lloyd) and, later, in Fiesole, Italy, where he lived with Mamah. During this time, Edwin Cheney granted Mamah a divorce, although Frank's wife Catherine refused to grant him one.[78] After Wright returned to the United States in October 1910, he persuaded his mother to buy land for him in Spring Green, Wisconsin. The land, bought on April 10, 1911, was adjacent to land held by his mother's family, the Lloyd-Joneses. Wright began to build himself a new home, which he called Taliesin, by May 1911. The recurring theme of Taliesin also came from his mother's side: Taliesin was a Welsh poet, magician, and priest. The family motto, "Y Gwir yn Erbyn y Byd" ("The Truth Against the World"), was taken from the Welsh poet Iolo Morganwg, who also had a son named Taliesin. The motto is still used today as the cry of the druids and chief bard of the Eisteddfod in Wales.[79]

Tragedy at Taliesin

[edit]

On August 15, 1914, while Wright was working in Chicago, Julian Carlton, a servant, set fire to the living quarters of Taliesin and then murdered seven people with an axe as the fire burned.[80][81][82] The dead included Mamah; her two children, John and Martha Cheney; a gardener (David Lindblom); a draftsman (Emil Brodelle); a workman (Thomas Brunker); and another workman's son (Ernest Weston). Two people survived, one of whom, William Weston, helped to put out the fire that almost completely consumed the residential wing of the house. Carlton swallowed hydrochloric acid following the attack in an attempt to kill himself.[81] He was nearly lynched on the spot, but was taken to the Dodgeville jail.[81] Carlton died from starvation seven weeks after the attack.

Divorces

[edit]In 1922, Kitty Wright finally granted Wright a divorce. Under the terms of the divorce, Wright was required to wait one year before he could marry his then-mistress, Maude "Miriam" Noel. In 1923, Wright's mother, Anna (Lloyd Jones) Wright, died. Wright wed Miriam Noel in November 1923, but her addiction to morphine led to the failure of the marriage in less than one year.[83] In 1924, after the separation, but while still married, Wright met Olga (Olgivanna) Lazovich Hinzenburg. They moved in together at Taliesin in 1925, and soon after Olgivanna became pregnant. Their daughter, Iovanna, was born on December 3, 1925.[84][85]

On April 20, 1925, another fire destroyed the bungalow at Taliesin. Crossed wires from a newly installed telephone system were deemed to be responsible for the blaze, which destroyed a collection of Japanese prints that Wright estimated to be worth $250,000 to $500,000 ($4,343,000 to $8,687,000 in 2023).[86] Wright rebuilt the living quarters, naming the home "Taliesin III".[87]

In 1926, Olga's ex-husband, Vlademar Hinzenburg, sought custody of his daughter, Svetlana. In October 1926, Wright and Olgivanna were accused of violating the Mann Act and were arrested in Tonka Bay, Minnesota.[88] The charges were later dropped.[89]

The divorce of Wright and Miriam Noel was finalized in 1927. Wright was again required to wait for one year before remarrying. Wright and Olgivanna married in 1928.[90][91]

Later career

[edit]Taliesin Fellowship

[edit]In 1932, Wright and his wife Olgivanna put out a call for students to come to Taliesin to study and work under Wright while they learned architecture and spiritual development. Olgivanna Wright had been a student of G. I. Gurdjieff who had previously established a similar school. Twenty-three came to live and work that year, including John (Jack) H. Howe, who would become Wright's chief draftsman.[92] A total of 625 people joined The Fellowship in Wright's lifetime.[93] The Fellowship was a source of workers for Wright's later projects, including: Fallingwater; The Johnson Wax Headquarters; and The Guggenheim Museum in New York City.[94]

Considerable controversy exists over the living conditions and education of the fellows.[95][96] Wright was reputedly a difficult person to work with. One apprentice wrote: "He is devoid of consideration and has a blind spot regarding others' qualities. Yet I believe, that a year in his studio would be worth any sacrifice."[97] The Fellowship evolved into The School of Architecture at Taliesin which was an accredited school until it closed under acrimonious circumstances in 2020.[98][99] Taking on the name "The School of Architecture" in June 2020, the school moved to the Cosanti Foundation, which it had worked with in the past.[100]

Usonian Houses

[edit]

Wright is responsible for a series of concepts of suburban development united under the term Broadacre City. He proposed the idea in his book The Disappearing City in 1932 and unveiled a 12-square-foot (1.1 m2) model of this community of the future, showing it in several venues in the following years.[citation needed] Concurrent with the development of Broadacre City, also referred to as Usonia, Wright conceived a new type of dwelling that came to be known as the Usonian House. Although an early version of the form can be seen in the Malcolm Willey House (1934) in Minneapolis, the Usonian ideal emerged most completely in the Herbert and Katherine Jacobs First House (1937) in Madison, Wisconsin.[citation needed] Designed on a gridded concrete slab that integrated the house's radiant heating system, the house featured new approaches to construction, including walls composed of a "sandwich" of wood siding, plywood cores and building paper – a significant change from typically framed walls.[citation needed] Usonian houses commonly featured flat roofs and were usually constructed without basements or attics, all features that Wright had been promoting since the early 20th century.[101]

Usonian houses were Wright's response to the transformation of domestic life that occurred in the early 20th century when servants had become less prominent or completely absent from most American households. By developing homes with progressively more open plans, Wright allotted the woman of the house a "workspace", as he often called the kitchen, where she could keep track of and be available for the children and/or guests in the dining room.[102] As in the Prairie Houses, Usonian living areas had a fireplace as a point of focus. Bedrooms, typically isolated and relatively small, encouraged the family to gather in the main living areas. The conception of spaces instead of rooms was a development of the Prairie ideal.[citation needed] The built-in furnishings related to the Arts and Crafts movement's principles that influenced Wright's early work.[citation needed] Spatially and in terms of their construction, the Usonian houses represented a new model for independent living and allowed dozens of clients to live in a Wright-designed house at relatively low cost.[citation needed] His Usonian homes set a new style for suburban design that influenced countless postwar developers. Many features of modern American homes date back to Wright: open plans, slab-on-grade foundations, and simplified construction techniques that allowed more mechanization and efficiency in construction.[103]

Significant later works

[edit]

Fallingwater, one of Wright's most famous private residences (completed 1937), was built for Mr. and Mrs. Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr., at Mill Run, Pennsylvania. Constructed over a 20-foot waterfall, it was designed according to Wright's desire to place the occupants close to the natural surroundings. The house was intended to be more of a family getaway, rather than a live-in home.[104] The construction is a series of cantilevered balconies and terraces, using sandstone for all verticals and concrete for the horizontals. The house cost $155,000 (equivalent to $3,285,000 in 2023), including the architect's fee of $8,000 (equivalent to $170,000 in 2023). It was one of Wright's most expensive pieces.[104] Kaufmann's own engineers argued that the design was not sound. They were overruled by Wright, but the contractor secretly added extra steel to the horizontal concrete elements. In 1994, Robert Silman and Associates examined the building and developed a plan to restore the structure. In the late 1990s, steel supports were added under the lowest cantilever until a detailed structural analysis could be done. In March 2002, post-tensioning of the lowest terrace was completed.[105]

Taliesin West, Wright's winter home and studio complex in Scottsdale, Arizona, was a laboratory for Wright from 1937 to his death in 1959. It is now the home of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.[106]

The design and construction of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City occupied Wright from 1943 until 1959[107] and is probably his most recognized masterpiece. The building's unique central geometry allows visitors to experience Guggenheim's collection of nonobjective geometric paintings by taking an elevator to the top level and then viewing artworks by walking down the slowly descending, central spiral ramp.

The only realized skyscraper designed by Wright is the Price Tower, a 19-story tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. It is also one of the two existing vertically oriented Wright structures (the other is the S.C. Johnson Wax Research Tower in Racine, Wisconsin). The Price Tower was commissioned by Harold C. Price of the H. C. Price Company, a local oil pipeline and chemical firm. On March 29, 2007, Price Tower was designated a National Historic Landmark by the United States Department of the Interior, one of only 20 such properties in Oklahoma.[108]

Monona Terrace, originally designed in 1937 as municipal offices for Madison, Wisconsin, was completed in 1997 on the original site, using a variation of Wright's final design for the exterior, with the interior design altered by its new purpose as a convention center. The "as-built" design was carried out by Wright's apprentice Tony Puttnam. Monona Terrace was accompanied by controversy until the structure was completed.[109]

Florida Southern College, located in Lakeland, Florida, constructed 12 (out of 18 planned) Frank Lloyd Wright buildings between 1941 and 1958 as part of the Child of the Sun project. It is the world's largest single-site collection of Frank Lloyd Wright architecture.[110]

Personal style and concepts

[edit]Design elements

[edit]

His Prairie houses use themed, coordinated design elements (often based on plant forms) that are repeated in windows, carpets, and other fittings. He made innovative use of new building materials such as precast concrete blocks, glass bricks, and zinc cames (instead of the traditional lead) for his leadlight windows, and he famously used Pyrex glass tubing as a major element in the Johnson Wax Headquarters.[citation needed] Wright was also one of the first architects to design and install custom-made electric light fittings, including some of the first electric floor lamps, and his very early use of the then-novel spherical glass lampshade (a design previously not possible due to the physical restrictions of gas lighting).[citation needed] In 1897, Wright received a patent for "Prism Glass Tiles" that were used in storefronts to direct light toward the interior.[111] Wright fully embraced glass in his designs and found that it fit well into his philosophy of organic architecture. According to Wright's organic theory, all components of the building should appear unified, as though they belong together. Nothing should be attached to it without considering the effect on the whole. To unify the house to its site, Wright often used large expanses of glass to blur the boundary between the indoors and outdoors.[112] Glass allowed for interaction and viewing of the outdoors while still protecting from the elements. In 1928, Wright wrote an essay on glass in which he compared it to the mirrors of nature: lakes, rivers and ponds.[113] One of Wright's earliest uses of glass in his works was to string panes of glass along whole walls in an attempt to create light screens to join solid walls. By using this large amount of glass, Wright sought to achieve a balance between the lightness and airiness of the glass and the solid, hard walls. Arguably, Wright's best-known art glass is that of the Prairie style. The simple geometric shapes that yield to very ornate and intricate windows represent some of the most integral ornamentation of his career.[114] Wright also designed some of his own clothing.[115]

Influences and collaborations

[edit]

Wright, an individualist, did not affiliate with the American Institute of Architects during his career; he called the organization "a harbor of refuge for the incompetent" and "a form of refined gangsterism".[116] When an associate referred to him as "an old amateur" Wright confirmed, "I am the oldest."[117] Wright rarely credited any influences on his designs, but most architects, historians and scholars agree he had five major influences:[citation needed]

- Louis Sullivan, whom he considered to be his lieber Meister (dear master)

- Nature, particularly shapes/forms and colors/patterns of plant life

- Music (his favorite composer was Ludwig van Beethoven)

- Japanese art, prints and buildings

- Froebel gifts[118]

Wright was given a set of Froebel gifts at about age nine, and in his autobiography he cited them indirectly in explaining that he learned the geometry of architecture in kindergarten play:

For several years I sat at the little kindergarten table-top ruled by lines about four inches apart each way making four-inch squares; and, among other things, played upon these 'unit-lines' with the square (cube), the circle (sphere) and the triangle (tetrahedron or tripod)—these were smooth maple-wood blocks. All are in my fingers to this day.[119]: 359

Wright later wrote, "The virtue of all this lay in the awakening of the child-mind to rhythmic structures in Nature… I soon became susceptible to constructive pattern evolving in everything I saw."[120]: 25 [121]: 205

He routinely claimed the work of architects and architectural designers who were his employees as his own designs, and believed that the rest of the Prairie School architects were merely his followers, imitators, and subordinates.[122] As with any architect, though, Wright worked in a collaborative process and drew his ideas from the work of others. In his earlier days, Wright worked with some of the top architects of the Chicago School, including Sullivan. In his Prairie School days, Wright's office was populated by many talented architects, including William Eugene Drummond, John Van Bergen, Isabel Roberts, Francis Barry Byrne, Albert McArthur, Marion Mahony Griffin, and Walter Burley Griffin. The Czech-born architect Antonin Raymond worked for Wright at Taliesin and led the construction of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. He subsequently stayed in Japan and opened his own practice. Rudolf Schindler also worked for Wright on the Imperial Hotel and his own work is often credited as influencing Wright's Usonian houses. Schindler's friend Richard Neutra also worked briefly for Wright. In the Taliesin days, Wright employed many architects and artists who later become notable, such as Aaron Green, John Lautner, E. Fay Jones, Henry Klumb, William Bernoudy, and Paolo Soleri.

Japanese art

[edit]Right — An archetypal gongen-zukuri shrine.

Wright was a passionate Japanophile — he once proclaimed Japan to be "the most romantic, artistic, nature-inspired country on earth."[123] He was particularly interested in ukiyo-e woodblock prints, to which he claimed he was "enslaved."[124] Wright spent much of his free time selling, collecting, and appreciating these prints. He held parties and other events centered around them, proclaiming their pedagogical value to his guests and students.[124] Before arriving in Japan, his impressions of the nation were based almost entirely on them.[123][125]

Wright found particular inspiration in the formal aspects of Japanese art. He described ukiyo-e prints as "organic," because of their understated qualities, their harmony, and their ability to be appreciated on a purely aesthetic level.[125] Additionally, he cherished their free-form compositions, where elements of the scene would frequently breach in front of one another, and their lack of extraneous detail, which he called a "gospel of elimination."[123][126] His interpretation of chashitsu (tea ceremony venues), mediated by the ideas of Okakura Kakuzō, was of an architecture that emphasized openness, the "vacant space between the roof and walls."[127][a] Wright applied these principles on a large scale, and they became trademarks of his practice.

Wright's floor plans exhibit strong similarities to their presumed Japanese forebears. The open living spaces of his early homes were likely appropriated from the World's Columbian Exposition's Ho-O-Den Pavilion, whose sliding-screen dividers were removed in preparation for the event.[128] Likewise, Unity Temple follows a gongen-zukuri layout, characteristic of Shinto shrines and likely inspired by his 1905 visit to the Rinnō-ji temple complex,[129] and the shape of many of his cantilevered towers, including the Johnson Research Tower, may have been inspired by Japanese pagodas.[130] Wright's ornamental flourishes, as seen in his leaded glass windows and lively architectural drawings, demonstrate a technical indebtedness to ukiyo-e.[126] One modern commentator, discussing the Robie House, suggests that such elements combined allow Wright's architecture to exhibit iki, a particularly Japanese aesthetic value marked by a subdued stylishness.[131]

His ideas about the art of Japan appear to have drawn greatly from the activities of Ernest Fenollosa, whose work he likely first encountered between 1890 and 1893.[132] Many of Fenollosa's ideas are quite similar to those of Wright: these include his view of architecture as a "mother art," his condemnation of the West's "separation of construction and decoration," and his identification of an "organic wholeness" within ukiyo-e prints.[126][132] Also like Wright, Fenollosa perceived a "degeneracy" in Western architecture, with particular emphasis on Renaissance architecture; Wright himself admitted that Japanese prints helped to "vulgarize" the Renaissance for him.[132] Wright's art criticism treatise, The Japanese Print: An Interpretation, may be read as a straightforward expansion upon Fenollosa's ideas.[126][132]

Though Wright always acknowledged his indebtedness to Japanese art and architecture, he took offense to claims that he copied or adapted it. In his view, Japanese art simply validated his personal principles especially well, and as such it was not a source of special inspiration.[125] Responding to a claim by Charles Robert Ashbee that he was "trying to adapt Japanese forms to the United States," Wright said that such borrowing was "against [his] very religion."[133] Nonetheless, his insistence did not stop others from observing the same throughout his life.

Art collecting and dealing

[edit]

Wright was also an active dealer in Japanese art, primarily ukiyo-e. He frequently served as both architect and art dealer to the same clients: he designed a home, then provided the art to fill it.[134] For a time, Wright made more from selling art than from his work as an architect. He also kept a personal collection, which he used as a teaching aid with his apprentices in what were called "print parties";[124][135] to better suit his taste, he sometimes modified these personal prints using colored pencils and crayons.[125] Wright owned prints from masters such as Okumura Masanobu, Torii Kiyomasu I, Katsukawa Shunshō, Utagawa Toyoharu, Utagawa Kunisada, Katsushika Hokusai, and Utagawa Hiroshige;[125] he was especially fond of Hiroshige, whom he considered "the greatest artist in the world."[124]

Wright first traveled to Japan in 1905, where he bought hundreds of prints. The following year, he helped organize the world's first retrospective exhibition on Hiroshige, held at the Art Institute of Chicago,[134] a job that strengthened his reputation as an expert in Japanese art.[125] Wright continued buying prints in his return trips to Japan[125] and for many years he was a major presence in the art world, selling a great number of works both to prominent private collectors[134] and to museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[136] In sum, Wright spent more than $500,000 on prints between 1905 and 1923.[137] He penned a book on Japanese art, The Japanese Print: An Interpretation, in 1912.[123][136]

In 1920, many of the prints Wright sold had been found to exhibit signs of retouching, including pinholes and unoriginal pigments.[125][137] These retouched prints were likely made in retribution by some of his Japanese dealers, who were disgruntled by the architect's under-the-table sales.[125] In an attempt to clear his name, Wright took one of his dealers, Kyūgo Hayashi, to court over the issue; Hayashi was subsequently sentenced to one year in prison, and barred from selling prints for an extended period of time.[125]

Though Wright protested his innocence, and provided his clients with genuine prints as replacements for those he was accused of retouching, the incident marked the end of the high point of his career as an art dealer.[136] He was forced to sell off much of his art collection to pay off outstanding debts: in 1928, the Bank of Wisconsin claimed Taliesin and sold thousands of his prints — for only one dollar a piece — to collector Edward Burr Van Vleck.[134] Nonetheless, Wright continued to collect and deal in prints until his death in 1959, using them as bartering chips and collateral for loans; he often relied upon his art business to remain financially solvent.[136] He once claimed that Taliesin I and II were "practically built" by his prints.[137]

The extent of his dealings in Japanese art went largely unknown, or underestimated, among art historians for decades. In 1980, Julia Meech, then associate curator of Japanese art at the Metropolitan Museum, began researching the history of the museum's collection of Japanese prints. She discovered "a three-inch-deep 'clump of 400 cards' from 1918, each listing a print bought from the same seller — 'F. L. Wright'" — and a number of letters exchanged between Wright and the museum's first curator of Far Eastern Art, Sigisbert C. Bosch Reitz. These discoveries and subsequent research led to a renewed understanding of Wright's career as an art dealer.[136]

Community planning

[edit]Frank Lloyd Wright's commissions and theories on urban design began as early as 1900 and continued until his death. He had 41 commissions on the scale of community planning or urban design.[138]

His thoughts on suburban design started in 1900 with a proposed subdivision layout for Charles E. Roberts entitled the "Quadruple Block Plan". This design strayed from traditional suburban lot layouts and set houses on small square blocks of four equal-sized lots surrounded on all sides by roads instead of straight rows of houses on parallel streets. The houses, which used the same design as published in "A Home in a Prairie Town" from the Ladies' Home Journal, were set toward the center of the block to maximize the yard space and included private space in the center. This also allowed for far more interesting views from each house. Although this plan was never realized, Wright published the design in the Wasmuth Portfolio in 1910.[139]

The more ambitious designs of entire communities were exemplified by his entry into the City Club of Chicago Land Development Competition in 1913. The contest was for the development of a suburban quarter section. This design expanded on the Quadruple Block Plan and included several social levels. The design shows the placement of the upscale homes in the most desirable areas and the blue collar homes and apartments separated by parks and common spaces. The design also included all the amenities of a small city: schools, museums, markets, etc.[140] This view of decentralization was later reinforced by theoretical Broadacre City design. The philosophy behind his community planning was decentralization. The new development must be away from the cities. In this decentralized America, all services and facilities could coexist "factories side by side with farm and home".[141]

Notable community planning designs:

- 1900–03 – Quadruple Block Plan, 24 homes in Oak Park, Illinois (unbuilt);

- 1909 – Como Orchard Summer Colony, town site development for new town in the Bitterroot Valley, Montana;

- 1913 – Chicago Land Development competition, suburban Chicago quarter section;

- 1934–59 – Broadacre City, theoretical decentralized city plan, exhibits of large-scale model;

- 1938 – Suntop Homes, also known as Cloverleaf Quadruple Housing Project – commission from Federal Works Agency, Division of Defense Housing, a low-cost multifamily housing alternative to suburban development;

- 1942 – Cooperative Homesteads, commissioned by a group of auto workers, teachers and other professionals, 160-acre farm co-op was to be the pioneer of rammed earth and earth berm construction[142] (unbuilt);

- 1945 – Usonia Homes, 47 homes (three designed by Wright) in Pleasantville, New York;

- 1949 – Parkwyn Village, a plat in Kalamazoo, Michigan, developed by Wright containing mostly Usonian houses by other architects with four by Wright. The community was planned to be on circular lots but was re-platted and squared off.

- 1949 – The Acres, also known as Galesburg Country Homes, with five houses (four designed by Wright) in Charleston Township, Michigan; The Acres remains the sole example of a planned community that has not had its circular lots squared off or been sub-divided.

Legacy

[edit]Death

[edit]

On April 4, 1959, Wright was hospitalized for abdominal pains and was operated upon. Wright seemed to be recovering but he died quietly on April 9 at the age of 91 years. The New York Times then reported he was 89.[143][144]

After his death, Wright's legacy was engulfed in turmoil for years. His third wife Olgivanna's dying wish had been that she, Wright, and her daughter by her first marriage would all be cremated and interred together in a memorial garden being built at Taliesin West. According to his own wishes, Wright's body had lain in the Lloyd-Jones cemetery, next to the Unity Chapel, within view of Taliesin in Wisconsin. Although Olgivanna had taken no legal steps to move Wright's remains (and against the wishes of other family members and the Wisconsin legislature), his remains were removed from his grave in 1985 by members of the Taliesin Fellowship. They were cremated and sent to Scottsdale where they were later interred as per Olgivanna's instructions. The original grave site in Wisconsin is now empty but is still marked with Wright's name.[145]

Archives

[edit]

After Wright's death, most of his archives were stored at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in Taliesin (in Wisconsin), and Taliesin West (in Arizona). These collections included more than 23,000 architectural drawings, some 44,000 photographs, 600 manuscripts, and more than 300,000 pieces of office and personal correspondence. It also contained about 40 large-scale architectural models, most of which were constructed for MoMA's retrospective of Wright in 1940.[146] In 2012, to guarantee a high level of conservation and access, as well as to transfer the considerable financial burden of maintaining the archive,[147] the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation partnered with the Museum of Modern Art and the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library of Columbia University to move the archive's content to New York. Wright's furniture and art collection remains with the foundation, which will also have a role in monitoring the archive. These three parties established an advisory group to oversee exhibitions, symposiums, events, and publications.[146]

Photographs and other archival materials are held by the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago. The architect's personal archives are located at Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona. The Frank Lloyd Wright archives include photographs of his drawings, indexed correspondence beginning in the 1880s and continuing through Wright's life, and other ephemera. The Getty Research Center, Los Angeles, also has copies of Wright's correspondence and photographs of his drawings in their Frank Lloyd Wright Special Collection. Wright's correspondence is indexed in An Index to the Taliesin Correspondence, ed. by Professor Anthony Alofsin, which is available at larger libraries.

Destroyed Wright buildings

[edit]

Wright designed more than 400 built structures,[148] of which about 300 survived as of 2023[update].[citation needed] At least five have been lost to forces of nature: the waterfront house for W. L. Fuller in Pass Christian, Mississippi, destroyed by Hurricane Camille in August 1969; the Louis Sullivan Bungalow of Ocean Springs, Mississippi, destroyed by Hurricane Katrina in 2005; and the Arinobu Fukuhara House (1918) in Hakone, Japan, destroyed in the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. In January 2006, the Wilbur Wynant House in Gary, Indiana was destroyed by fire.[149] In 2018 the Arch Oboler complex in Malibu, California was gutted in the Woolsey Fire.[150]

Many other notable Wright buildings were intentionally demolished: Midway Gardens (built 1913, demolished 1929), the Larkin Administration Building (built 1903, demolished 1950), the Francis Apartments and Francisco Terrace Apartments (Chicago, built 1895, demolished 1971 and 1974, respectively), the Geneva Inn (Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, built 1911, demolished 1970), and the Banff National Park Pavilion (built 1914, demolished 1934). The Imperial Hotel (built 1923) survived the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, but was demolished in 1968 due to urban developmental pressures.[151] The Hoffman Auto Showroom in New York City (built 1954) was demolished in 2013.[152]

Unbuilt and posthumously built

[edit]

Several of Wright's projects either were built after his death or remain unbuilt. These include:

- Crystal Heights, a large mixed-use development in Washington, D.C., 1940 (unbuilt)

- The Illinois, mile-high tower in Chicago, 1956 (unbuilt)

- Marin County Civic Center, a municipal complex in San Rafael, California; groundbreaking occurred just one year after Wright's death

- Monona Terrace, convention center in Madison, Wisconsin; designed 1938–1959, built in 1997

- Clubhouse at the Nakoma Golf Resort, Plumas County, California; designed in 1923, opened in 2000

- Passive Solar Hemi-Cycle Home in Hawaii; designed in 1954, built in 1995

Recognition

[edit]

Later in his life (and after his death in 1959), Wright was accorded significant honorary recognition for his lifetime achievements. He received a Gold Medal award from The Royal Institute of British Architects in 1941. The American Institute of Architects awarded him the AIA Gold Medal in 1949. That medal was a symbolic "burying the hatchet" between Wright and the AIA. In a radio interview, he commented, "Well, the AIA I never joined, and they know why. When they gave me the gold medal in Houston, I told them frankly why. Feeling that the architecture profession is all that's the matter with architecture, why should I join them?"[117] He was awarded the Franklin Institute's Frank P. Brown Medal in 1953. He received honorary degrees from several universities (including his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin), and several nations named him as an honorary board member to their national academies of art and/or architecture. In 2000, Fallingwater was named "The Building of the 20th century" in an unscientific "Top-Ten" poll taken by members attending the AIA annual convention in Philadelphia.[citation needed] On that list, Wright was listed along with many of the USA's other greatest architects including Eero Saarinen, I.M. Pei, Louis Kahn, Philip Johnson, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe; he was the only architect who had more than one building on the list. The other three buildings were the Guggenheim Museum, the Frederick C. Robie House, and the Johnson Wax Building.

In 1992, the Madison Opera in Madison, Wisconsin, commissioned and premiered the opera Shining Brow, by composer Daron Hagen and librettist Paul Muldoon based on events early in Wright's life. The work has since received numerous revivals, including a June 2013 revival at Fallingwater, in Bull Run, Pennsylvania, by Opera Theater of Pittsburgh. In 2000, Work Song: Three Views of Frank Lloyd Wright, a play based on the relationship between the personal and working aspects of Wright's life, debuted at the Milwaukee Repertory Theater.

In 1966, the United States Postal Service honored Wright with a Prominent Americans series 2¢ postage stamp.[153]

"So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright" is a song written by Paul Simon. Art Garfunkel has stated that the origin of the song came from his request that Simon write a song about the famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Simon himself stated that he knew nothing about Wright, but proceeded to write the song anyway.[154]

In 1957, Arizona made plans to construct a new capitol building. Believing that the submitted plans for the new capitol were tombs to the past, Frank Lloyd Wright offered Oasis as an alternative to the people of Arizona.[155] In 2004, one of the spires included in his design was erected in Scottsdale.[156]

The city of Scottsdale, Arizona renamed a portion of Bell Road, a major east–west thoroughfare in the Phoenix metropolitan area, in honor of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Eight of Wright's buildings – Fallingwater, the Guggenheim Museum, the Hollyhock House, the Jacobs House, the Robie House, Taliesin, Taliesin West, and the Unity Temple – were inscribed on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites under the title The 20th-century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright in July 2019. UNESCO stated that these buildings were "innovative solutions to the needs for housing, worship, work or leisure" and "had a strong impact on the development of modern architecture in Europe".[157][158]

Family

[edit]Frank Lloyd Wright was married three times, fathering four sons and three daughters. He also adopted Svetlana Milanoff, the daughter of his third wife, Olgivanna Lloyd Wright.[159]

His wives/partners were:

- Catherine "Kitty" (Tobin) Wright (1871–1959); social worker, socialite (married in June 1889; divorced November 1922)

- Martha Bouton "Mamah" Borthwick (June 19, 1869 – August 15, 1914) was an American translator who had a romantic relationship with architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1909–1914), which ended when she was murdered after a male servant set fire to the living quarters of Taliesin and murdered seven people with an axe as they fled the burning structure.

- Maude "Miriam" (Noel) Wright (1869–1930), artist (married in November 1923; divorced August 1927)

- Olga Ivanovna "Olgivanna" (Lazovich Milanoff) Lloyd Wright (1897–1985), dancer and writer (married in August 1928)

His children with Catherine were:

- Frank Lloyd Wright Jr., known as Lloyd Wright (1890–1978), became a notable architect in Los Angeles. Lloyd's son, Eric Lloyd Wright (1929–2023), was an architect in Malibu, California, specializing in residences, but also designed civic and commercial buildings.

- John Lloyd Wright (1892–1972), invented Lincoln Logs in 1918, and practiced architecture extensively in the San Diego area. John's daughter, Elizabeth Wright Ingraham (1922–2013), was an architect in Colorado Springs, Colorado. She was the mother of Christine, an interior designer in Connecticut, and Catherine, an architecture professor at the Pratt Institute.[160]

- Catherine Wright Baxter (1894–1979) was a homemaker and the mother of Oscar-winning actress Anne Baxter. Anne Baxter is the mother of Melissa Galt, an interior designer in Scottsdale, Arizona.

- David Samuel Wright (1895–1997) was a building-products representative for whom Wright designed the David & Gladys Wright House, which was rescued from demolition and given to the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture.[161][162][163]

- Frances Wright Caroe (1898–1959) was an arts administrator.

- Robert Llewellyn Wright (1903–1986) was an attorney for whom Wright designed a house in Bethesda, Maryland.[164]

His children with Olgivanna were:

- Svetlana Peters (1917–1946, adopted daughter of Olgivanna) was a musician who died in an automobile accident with her son Daniel. After Svetlana's death her other son, Brandoch Peters (1942– ), was raised by Frank and Olgivanna. Svetlana's widower, William Wesley Peters, was later briefly married to Svetlana Alliluyeva, the youngest child and only daughter of Joseph Stalin. William Wesley Peters served as chairman of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation from 1985 to 1991.

- Iovanna Lloyd Wright (1925–2015) was an artist and musician.

Selected works

[edit]Books

[edit]- Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright (Wasmuth Portfolio) (1910)

- An Organic Architecture: The Architecture of Democracy (1939)

- In the Cause of Architecture: Essays by Frank Lloyd Wright for Architectural Record 1908–1952 (1987)

- Visions of Wright: Photographs by Farrell Grehan, Introduction by Terence Riley ISBN 0-8212-2470-0 (1997)

Buildings

[edit]- Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio, Oak Park, Illinois, 1889–1909

- Winslow House, River Forest, Illinois, 1894

- Frank Thomas House, Oak Park, Illinois, 1901

- Ward Winfield Willits Residence, and Gardener's Cottage and Stables, Highland Park, Illinois, 1901

- Dana–Thomas House, Springfield, Illinois, 1902

- Larkin Administration Building, Buffalo, New York, 1903 (demolished, 1950)

- Darwin D. Martin House, Buffalo, New York, 1903–1905

- Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois, 1904

- Dr. G.C. Stockman House, Mason City, Iowa, 1908

- Edward E. Boynton House, Rochester, New York, 1908

- Frederick C. Robie Residence, Chicago, Illinois, 1909

- Park Inn Hotel, the last standing Wright designed hotel, Mason City, Iowa, 1910

- Taliesin, Spring Green, Wisconsin, 1911 & 1925

- Midway Gardens, Chicago, Illinois, 1913 (demolished, 1929)

- Hollyhock House (Aline Barnsdall Residence), Los Angeles, 1919–1921

- Ennis House, Los Angeles, 1923

- Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, Japan, 1923 (demolished, 1968; entrance hall reconstructed at Meiji Mura near Nagoya, Japan, 1976)

- Westhope (Richard Lloyd Jones Residence), Tulsa, Oklahoma, 1929

- Malcolm Willey House 1934, Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Fallingwater (Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr. Residence), Mill Run, Pennsylvania, 1935–1937

- Johnson Wax Headquarters, Racine, Wisconsin, 1936

- First Jacobs House, Madison, Wisconsin, 1936–1937

- Usonian homes, various locations, 1930s–1950s

- Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona, 1937

- Wingspread, Herbert F. Johnson Residence in Wind Point, Wisconsin, 1937

- Pope–Leighey House, Alexandria, Virginia, 1941

- Child of the Sun, Florida Southern College, Lakeland, Florida, 1941–1958, site of the largest collection of the architect's work

- First Unitarian Society of Madison, Shorewood Hills, Wisconsin, 1947

- V. C. Morris Gift Shop, San Francisco, 1948

- Kenneth and Phyllis Laurent House, Rockford, Illinois, only home Wright designed to be handicapped accessible, 1951

- Price Tower, Bartlesville, Oklahoma, 1952–1956

- Beth Sholom Synagogue, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, 1954

- Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church, Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, 1956–1961

- Kentuck Knob, Ohiopyle, Pennsylvania, 1956

- Marshall Erdman Prefab Houses, various locations, 1956–1960

- Marin County Civic Center, San Rafael, California, 1957–1966

- R. W. Lindholm Service Station, Cloquet, Minnesota, 1958

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, 1956–1959

- Gammage Memorial Auditorium, Tempe, Arizona, 1959–1964

See also

[edit]- Richard Bock

- Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy

- Frank Lloyd Wright-Prairie School of Architecture Historic District

- George Mann Niedecken

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works by location

- Jaroslav Joseph Polivka

- Roman brick

- The 20th-century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright (UNESCO World Heritage site)

- Category:Frank Lloyd Wright buildings

References

[edit]- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 777. ISBN 978-0-415-86287-5.

- ^ A Directory of Frank Lloyd Wright Associates: APPRENTICES 1929 to 1959 Archived September 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, jgonwright.net, accessed February 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Brewster, Mike (July 28, 2004). "Frank Lloyd Wright: America's Architect". Business Week. The McGraw-Hill Companies. Archived from the original on March 2, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ Hines, Thomas S. (1967). "Frank Lloyd Wright: The Madison Years: Records versus Recollections". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 50 (2): 109–119. ISSN 0043-6534. JSTOR 4634222.

- ^ Huxtable, Ada Louise (October 31, 2004). "'Frank Lloyd Wright'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ Gill, Brendan, Many Masks, a Life of Frank Lloyd Wright, Ballantine Books, 1987 p. 25.

- ^ Huxtable, Ada Louise (2008). Frank Lloyd Wright: A Life. Penguin. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4406-3173-3.

- ^ Kimber, Marian Wilson (2014). "Various Artists. The Music of William C. Wright: Solo Piano and Vocal Works, 1847–1893. Permelia Records 010225, 2013". Journal of the Society for American Music. 8 (2): 274–276. doi:10.1017/S1752196314000169. ISSN 1752-1963. S2CID 190701799.

- ^ Secrest, Meryle (1998). Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography. University of Chicago Press. p. 36.

- ^ Secrest, p. 58.

- ^ a b Huxtable, Ada Louise (October 31, 2004). "'Frank Lloyd Wright'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ Alofsin, Anthony (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright – the Lost Years, 1910–1922: A Study of Influence. University of Chicago Press. p. 359. ISBN 0-226-01366-9; Hersey, George (2000). Architecture and Geometry in the Age of the Baroque. University of Chicago Press. p. 205. ISBN 0-226-32783-3.

- ^ Hendrickson, Paul, Plagued By Fire, New York: Alfred A Knopf, 2019, p. 399.

- ^ Secrest, p. 72.

- ^ Wright, Frank Lloyd, An Autobiography, Duell, Sloan and Pearce, New York City, 1943, p. 51.

- ^ "Allan D[arst] Conover, architect". www.archinform.net.

- ^ Secrest, p. 82.

- ^ "Honorary Degree Recipients". Office of the Secretary of the Faculty. University of Wisconsin–Madison. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ Frank Lloyd Wright's Monona Terrace: The Enduring Power of a Civic Vision, by David V. Mollenhoff and Mary Jane Hamilton (The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin, 1999), p. 54.

- ^ a b Dean, Jeffrey M. (July 18, 1974), National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form: Unity Chapel, National Park Service, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, retrieved October 29, 2014

- ^ McCarter, Robert (1997). Frank Lloyd Wright. Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3148-0.

- ^ Wright, Frank Lloyd (2005). Frank Lloyd Wright: An Autobiography. Petaluma, CA: Pomegranate Communications. pp. 60–63. ISBN 978-0-7649-3243-4.

- ^ O'Gorman, Thomas J. (2004). Frank Lloyd Wright's Chicago. San Diego: Thunder Bay Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-1-59223-127-0.

- ^ It is often reported incorrectly that Wright worked Beers, Clay and Dutton, but Clay was at this time in private practice. The mistake is understandable as it is based on Wright's own account in his autobiography.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 69

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 66

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 83.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 86.

- ^ Wright 2005, pp. 89–94.

- ^ a b Tafel, Edgar (1985). Years With Frank lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-486-24801-1.

- ^ a b Saint, Andrew (May 2004). "Frank Lloyd Wright and Paul Mueller: the architect and his builder of choice" (PDF). Architectural Research Quarterly. 7 (2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 157–167. doi:10.1017/S1359135503002112. S2CID 108461943. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ a b Gebhard, David; Patricia Gebhard (2006). Purcell & Elmslie: Prairie Progressive Architects. Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4236-0005-3.

- ^ Brewer, Gregory M. (Spring 2024). "Frank Lloyd Wright's Berry-MacHarg House Revealed" (PDF). Nineteenth Century. 44 (1): 34–37.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Lind, Carla (1996). Lost Wright: Frank Lloyd Wright's Vanished Masterpieces. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. pp. 40–43. ISBN 978-0-684-81306-6.

- ^ Abrams, Garry (November 29, 1987). "Unmasking Frank Lloyd Wright". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ O'Gorman 2004, pp. 38–54.

- ^ "Kenwood's Double Shot of Frank Lloyd Wright". Chicago Magazine. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Dr. Allison Harlan House | Frank Lloyd Wright Trust". www.flwright.org. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "frank lloyd wright's 1892 harlan house documented shortly before its demolition after devastating fire in 1963". Urban Remains Chicago News and Events. June 13, 2022. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 101.

- ^ Tafel 1985, p. 41.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 119.

- ^ Brooks, H. Allen (2005). "Architecture: The Prairie School". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ Cassidy, Victor M. (October 21, 2005). "Lost Woman". Artnet Magazine. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ "Marion Mahony Griffin (1871–1962)". From Louis Sullivan to SOM: Boston Grads Go to Chicago. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1996. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ O'Gorman 2004, pp. 56–109.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 116.

- ^ Pulos, Arthur J. (April 22, 2021). "From Beaux-Arts to Arts and Crafts". MIT Press Open Architecture and Urban Studies.

- ^ Becker, Lynn (July 16, 2009). "An Odd Way to Honor Daniel Burnham". Chicago Reader. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ Wright 2005, pp. 114–116.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (March 9, 2009). "Toddlin' Town: Daniel Burnham's great Chicago Plan turns one hundred". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust 2001, pp. 6–9.

- ^ My Father: Frank Lloyd Wright, by John Lloyd Wright; 1992; p. 35.

- ^ a b Clayton, Marie (2002). Frank Lloyd Wright Field Guide. Running Press. pp. 97–102. ISBN 978-0-7624-1324-9.

- ^ Sommer, Robin Langley (1997). "Frank W. Thomas House". Frank Lloyd Wright: A Gatefold Portfolio. Hong Kong: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 978-0-7607-0463-9.

- ^ O'Gorman 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Silzer, Kate (September 10, 2019). "Architect Frank Lloyd Wright's 5 Key Works". Artsy. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ^ "Prairie School Architecture". www.antiquehome.org. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ^ Storrer, William Allin (2007). The architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright : a complete catalog (Updated 3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. xvii. ISBN 978-0-226-77620-0.

- ^ Secrest, p. 202.

- ^ "Wasmuth Portfolio – Volume 1 | Rare Books Collection". collections.lib.utah.edu. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Lui, Ann (January 29, 2009). "Cornell Architecture Myths: Busted". The Cornell Daily Sun. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ^ "Unity Temple | Frank Lloyd Wright Trust". flwright.org.

- ^ "Frank Lloyd Wright Houses: His 20 Most Famous Homes, Buildings & Studios". Architecture & Design. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Nute K. Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan: The Role of Traditional Japanese Art and Architecture in the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright. London, Routledge Publ., 2000.

- ^ 明石, 信道; 村井, 修 (2004). フランク・ロイド・ライトの帝国ホテル. 建築資料研究社. ISBN 978-4-87460-814-2.

- ^ ケヴィン, ニュート; Nute, Kevin (1997). フランク・ロイド・ライトと日本文化. Translated by 大木, 順子. 鹿島出版会. ISBN 978-4-306-04354-1.

- ^ "Imperial Hotel Lobby (Reconstruction)".

- ^ 谷川, 正己; 宮本, 和義 (2016). フランク・ロイド・ライト 自由学園明日館. バナナブックス. ISBN 978-4-902930-33-7.

- ^ "The Wright Building". Imperial Hotel Tokyo. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Jiyu Gakuen Myonichikan". Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Koyama, Hisao; Sergeant, John; Nute, Kevin (2000). Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan: The Role of Traditional Japanese Art and Architecture in the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-23269-2.

- ^ a b Wright, Frank Lloyd (2008). Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks (ed.). The Essential Frank Lloyd Wright: Critical Writings on Architecture. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14632-4. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ a b American Treasures of the Library of Congress. "The Genius of Frank Lloyd Wright". Library of Congress. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ Sanderson, Arlene, Wright Sites, Princeton Architectural Press, 1995, p. 16.

- ^ Hines, Thomas S. (2010). Architecture of the sun : Los Angeles modernism, 1900–1970. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-3320-7.

- ^ "The Massacre at Frank Lloyd Wright's 'Love Cottage'". HISTORY. August 11, 2023. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ^ "Home Country". Unitychapel.org. July 1, 2005. Archived from the original on December 28, 2005. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ Hendrickson, Paul, Plagued by Fire, Knopf, 2019, pp. 8, 194–97

- ^ a b c "Mystery of the murders at Taliesin". BBC News.

- ^ "Taliesin Massacre (Frank Lloyd Wright)".

- ^ "How Frank Lloyd Wright Worked". HowStuffWorks. September 22, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Iovanna Lloyd Wright Obituary (2015) New York Times". Legacy.com. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Friedland, Roger; Zellman, Harold. The Fellowship: The Untold Story of Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin. Harper Perennial. p. 104.

- ^ Secrest, pp. 315–317.

- ^ Brooks Pfeiffer, Bruce, ed. (1992). Frank Lloyd Wright. An Autobiography. Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings: 1930–32. Vol. 2. New York City: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. p. 295.

- ^ Welter, Ben (March 19, 2006). "Thursday, Oct. 21, 1926: Wright jailed in Minneapolis". Star Tribune. Yesterday's News. Minneapolis. Archived from the original on April 5, 2011.

- ^ Weiner, Eric (March 11, 2008). "The Long, Colorful History of the Mann Act". NPR.org. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Richard G. (October 1973). "An Organic Architecture, The Architecture of Democracy Frank Lloyd Wright Genius and the Mobocracy Frank Lloyd Wright The Industrial Revolution Runs Away Frank Lloyd Wright The Imperial Hotel, Frank Lloyd Wright and the Architecture of Unity Cary James Frank Lloyd Wright, Public Buildings Martin Pawley" (PDF). Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 32 (3): 262–263. doi:10.2307/988805. ISSN 0037-9808. JSTOR 988805.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (March 2, 1985). "Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, Wife of the Architect, Is Dead at 85". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ Hession, Jane and Quigley, Tim, John H. Howe, Architect, University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

- ^ A Directory of Frank Lloyd Wright Associates: APPRENTICES 1929 to 1959 Archived September 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine jgonwright.net, accessed February 10, 2021

- ^ Friedland, Roger, and Zellman, Harold. The Fellowship: The Untold Story of Frank Lloyd Wright & the Taliesin Fellowship. New York: Harper Perennial, 2007, p. 483

- ^ Friedland and Zellman, p. 197

- ^ Marty, Myron A., and Marty, Shirley L. Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin Fellowship. Kirksville, Mo: Truman State University Press, 1999.

- ^ Field, Marcus (March 8, 2009). "Architect of desire: Frank Lloyd Wright's private life was even more unforgettable than his buildings". The Independent. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ "Taliesin – Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture". taliesin.edu. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ^ "Frank Lloyd Wright's legacy to live on after School of Architecture closes". May 7, 2020.

- ^ Gifford, Jim, Phoenix Business Journal, June 17, 2020

- ^ Twombly, p. 242.

- ^ Twombly, p. 257.

- ^ Twombly, p. 244.

- ^ a b Twombly, Robert (1979). Frank Lloyd Wright His Life and Architecture. Canada: A Wiley-Interscience. pp. 276–278.

- ^ Matthew L. Wal, "Rescuing a World-Famous but Fragile House", New York Times, September 2, 2001.

- ^ "About Taliesin West". Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ "The Frank Lloyd Wright Building". November 10, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ^ National Park Service Archived November 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine – National Historic Landmarks Designated, April 13, 2007

- ^ "Monona Terrace Convention Center, history web page" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ^ "74 years later, Frank Lloyd Wright structure built at Florida Southern College". Building Design & Construction Magazine. October 31, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ^ Feo, Anthony de (May 3, 2017). "The Prismatic Glass Tiles of Frank Lloyd Wright". DailyArtMagazine.com – Art History Stories.