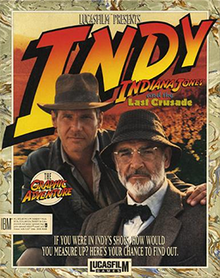

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure

| Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Lucasfilm Games |

| Publisher(s) | Lucasfilm Games |

| Designer(s) | Ron Gilbert Noah Falstein David Fox |

| Artist(s) | Steve Purcell Martin Cameron James A. Dollar Mike Ebert James McLeod |

| Composer(s) | Eric Hammond FM Towns: Dave Warhol James Leiterman |

| Engine | SCUMM |

| Platform(s) | MS-DOS, Amiga, Atari ST, Mac, FM Towns, CDTV |

| Release | July 1989: MS-DOS, Amiga, Atari ST 1990: Mac, FM Towns [1] 1992: CDTV July 08, 2009: Steam |

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure is a graphic adventure game, released in 1989 by Lucasfilm Games, coinciding with the release of the film of the same name. It was the third game to use the SCUMM engine.

Gameplay

[edit]

Last Crusade expanded on Lucasfilm Games' traditional adventure game structure by including a flexible point system—the IQ score, or "Indy Quotient"—and by allowing the game to be completed in several different ways.[1][2] The point system was similar to that of Sierra's adventure games, however when the game was restarted or restored, the total IQ of the previous game was retained. The only way to reach the maximum IQ of 800 was by finding alternative solutions to puzzles, such as fighting a guard instead of avoiding him.[1] This countered one common criticism of adventures games, whereby since there is only one way to finish the game, they have no replay value.[1][2] Also, the point system helped the game to appeal to a variety of player types. Some of the alternative fights, such as the one with the Zeppelin attendant, were very difficult to pass, so the maximum IQ was very difficult to achieve.

A replica of Henry Jones' Grail diary was included with earlier versions of the game.[2][3] While very different from the film's version, it provided a collection of background information of Indy's youth and Henry's life. The diary was also necessary to solve puzzles near the end of the game, most notably to identify the real Grail. Later versions of the game came with a shortened version of the Grail diary.

Plot

[edit]The plot closely follows, and expands upon, the film of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. As the game begins, Indiana Jones has returned to his college, after reclaiming the Cross of Coronado. He is approached by businessman Walter Donovan, who tells him about the Holy Grail, and of the disappearance of Indy's father.

Indy then travels to some of the places seen in the movie, such as Venice and the catacombs, after meeting fellow archeologist Elsa Schneider. In the process he finds his father held captive in the Brunwald Castle, after passing through the mazelike corridors, fighting and avoiding guards. Then Elsa's double role is revealed when she steals the Grail Diary from Indy. After escaping, father and son pass through Berlin to reclaim the Diary and have a brief meeting with Adolf Hitler. Then they reach an airport, from where they intend to seek the Valley of the Crescent Moon, by Zeppelin or biplane. There are many action scenes, involving punching, and the biplane sequence above Europe, pursued by Nazi planes.

Several key elements of the film - such as the Brotherhood of the Grail, Indy's friend Sallah, and the Venice water chase and the desert battle scenes (except for small hidden references) - were not included in the game.

Development

[edit]The game was released in May 1989 simultaneously with the movie. It was available for DOS, Amiga, Atari ST, and Mac OS. A CD-ROM version was later released for the FM Towns, with 256-color graphics and a CD Audio soundtrack, as well as a VGA PC version. Many of the scenes unique to the game were conceived by George Lucas and Steven Spielberg during the creation of the movie.[4] Last Crusade was also the first Lucasfilm game to include the verbs Look and Talk. In several situations, the latter would begin a primitive dialogue system in which the player could choose one of several lines to say. The system was fully evolved in The Secret of Monkey Island and remained in all later LucasArts adventures, with the exception of Loom.

Reception

[edit]UK magazine Computer and Video Games gave the PC version a score of 91%, praising the graphics, sound and playability and calling it "a brilliant film tie-in and a superlative game in its own right".[5] In 1989, Dragon gave the game 5 out of 5 stars.[6] The game was ranked the 28th best game of all time by Amiga Power.[7] Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World gave the game a positive review, noting its cinematic qualities and well-designed puzzles.[4] Game Informer's retro review section awarded the game a nine out of ten.

The Last Crusade became a "sizeable hit", according to Hal Barwood.[8] It was Lucasfilm's best-selling game at the time of its release, with sales of over 250,000 copies.[9]

In 1991, PC Format placed The Last Crusade on its list of the 50 best computer games of all time. The editors wrote that Indy was recreated on the monitor screen impressively as on the big screen.[10]

Further reading

[edit]- Jeux & Stratégie nouvelle formule #1[11]

Legacy

[edit]A second Indiana Jones graphic adventure, Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, was released in 1992.

Two supposed successors to Fate of Atlantis, Iron Phoenix and The Spear of Destiny, were canceled.[12] Both were later adapted into comics.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Bateman, Chris (2009). Beyond Game Design: Nine Steps Towards Creating Better Videogames. Cengage Learning. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0495926894. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c Losee, Stephanie (December 12, 1989). "Indiana Jones Takes His Crusade to Your Desktop". PC Magazine. Vol. 8, no. 21. p. 454. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ A Bibliography of Modern Arthuriana (1500-200). Boydell & Brewer. 2006. pp. 597–598. ISBN 9781843840688. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Ardai, Charles (November 1989). "Travels with Indy: Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure". Computer Gaming World. No. 65. pp. 72, 74.

- ^ Rignall, Julian (September 1989). "Indy Adventure". Computer and Video Games. No. 94. pp. 62–63.

- ^ Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (December 1989). "The Role of Computers". Dragon (152): 64–70.

- ^ Amiga Power magazine issue #0, Future Publishing, May 1991

- ^ Bevan, Mike (2008). "The Making of Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis". Retro Gamer Magazine (51). Imagine Publishing Ltd.: 44–49.

- ^ "Past Projects". Archived from the original on 2017-03-25.

- ^ Staff (October 1991). "The 50 best games EVER!". PC Format (1): 109–111.

- ^ "Jeux & stratégie NF 1". November 11, 1989 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Frank, Hans (July 18, 2007). "Interview: Hal Barwood". Adventure-Treff. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

External links

[edit]- 1989 video games

- Adventure games

- Amiga games

- Atari ST games

- Classic Mac OS games

- Commodore CDTV games

- DOS games

- FM Towns games

- Golden Joystick Award winners

- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade games

- Indiana Jones video games

- LucasArts games

- Point-and-click adventure games

- SCUMM games

- ScummVM-supported games

- Single-player video games

- U.S. Gold games

- Video game sequels

- Video games about Nazi Germany

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games set in Austria

- Video games set in Berlin

- Video games set in castles

- Video games set in New York (state)

- Video games set in New York City

- Video games set in Turkey

- Video games set in Venice