Astronomical symbols

Astronomical symbols are abstract pictorial symbols used to represent astronomical objects, theoretical constructs and observational events in European astronomy. The earliest forms of these symbols appear in Greek papyrus texts of late antiquity. The Byzantine codices in which many Greek papyrus texts were preserved continued and extended the inventory of astronomical symbols.[2][3] New symbols have been invented to represent many planets and minor planets discovered in the 18th to the 21st centuries.

These symbols were once commonly used by professional astronomers, amateur astronomers, alchemists, and astrologers. While they are still commonly used in almanacs and astrological publications, their occurrence in published research and texts on astronomy is relatively infrequent,[4] with some exceptions such as the Sun and Earth symbols appearing in astronomical constants, and certain zodiacal signs used to represent the solstices and equinoxes.

Unicode has encoded many of these symbols, mainly in the Miscellaneous Symbols,[5] Miscellaneous Symbols and Arrows,[6] Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs,[7] and Alchemical Symbols blocks.[8]

Symbols for the Sun and Moon

[edit]The use of astronomical symbols for the Sun and Moon dates to antiquity. The forms of the symbols that appear in the original papyrus texts of Greek horoscopes are a circle with one ray (![]() ) for the Sun and a crescent for the Moon.[3] The modern Sun symbol, a circle with a dot (☉), first appeared in Europe in the Renaissance.[3]

) for the Sun and a crescent for the Moon.[3] The modern Sun symbol, a circle with a dot (☉), first appeared in Europe in the Renaissance.[3]

-

The symbol for the Sun in late Classical (4th c.) and medieval Byzantine (11th c.) manuscripts[9]

-

The symbol for the Moon in a medieval Byzantine manuscript (11th c.). The late Classical appearance was similar.[9]

In modern academic writing, the Sun symbol is used for astronomical constants relating to the Sun.[10] Teff☉ represents the solar effective temperature, and the luminosity, mass, and radius of stars are often represented using the corresponding solar constants (L☉, M☉, and R☉, respectively) as units of measurement.[11][12][13][14]

| Referent | Symbol | Unicode code point |

Unicode display |

Represents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | [15][16] |

U+2609 (dec 9737) |

☉︎ | Standard astronomical symbol |

[3] |

U+1F71A (dec 128794) |

🜚︎ | the Sun with one ray | |

[17][18] |

U+1F31E (dec 127774) |

🌞︎︎ | the face of the Sun or "Sun in splendor" |

| Referent | Symbol | Unicode code point |

Unicode text display[20] |

Represents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moon | [21][22][23] |

U+263D (dec 9789) |

☽︎ | an increscent (waxing) moon (as viewed from the northern hemisphere) |

[22][23] |

U+263E (dec 9790) |

☾ | a decrescent (waning) moon (as viewed from the northern hemisphere) | |

| new moon | [22][23] |

U+1F311 (dec 127761) |

🌑︎ | fully dark |

[17][24][25] |

U+1F31A (dec 127770) |

🌚︎ | ||

| waxing crescent | U+1F312 (dec 127762) |

🌒︎ | encrescent moon (northern hemisphere) | |

| first-quarter (waxing) moon | U+1F313 (dec 127763) |

🌓︎ | one week into the month, half the visible face illuminated | |

[26] or [17][24][25] |

U+1F31B (dec 127771) |

🌛︎︎ | ||

| waxing gibbous | U+1F314 (dec 127764) |

🌔︎ | (northern hemisphere) | |

| full moon | [22][23] |

U+1F315 (dec 127765) |

🌕︎ | fully illuminated |

[17][24][25] |

U+1F31D (dec 127773) |

🌝︎︎ | ||

| waning gibbous | U+1F316 (dec 127766) |

🌖︎ | (northern hemisphere) | |

| last-quarter (waning) moon | U+1F317 (dec 127767) |

🌗︎ | final week of the month, the other half of the visible face illuminated | |

[26] or [17][24][25] |

U+1F31C (dec 127772) |

🌜︎︎ | ||

| waning crescent | U+1F318 (dec 127768) |

🌘︎ | decrescent moon (northern hemisphere) |

Symbols for the planets

[edit]

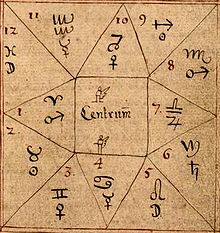

Symbols for the classical planets appear in many medieval Byzantine codices in which many ancient horoscopes were preserved.[2] The written symbols for Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn have been traced to forms found in late Greek papyrus texts.[9] The symbols for Jupiter and Saturn are identified as monograms of the corresponding Greek names, and the symbol for Mercury is a stylized caduceus.[9] According to A.S.D. Maunder, antecedents of the planetary symbols were used in art to represent the gods associated with the classical planets; Bianchini's planisphere, discovered by Francesco Bianchini in the 18th century, produced in the 2nd century,[27] shows Greek personifications of planetary gods charged with early versions of the planetary symbols: Mercury has a caduceus; Venus has, attached to her necklace, a cord connected to another necklace; Mars, a spear; Jupiter, a staff; Saturn, a scythe; the Sun, a circlet with rays radiating from it; and the Moon, a headdress with a crescent attached.[28]

A diagram in Byzantine astronomer Johannes Kamateros's 12th century Compendium of Astrology shows the Sun represented by the circle with a ray, Jupiter by the letter Zeta (the initial of Zeus, Jupiter's counterpart in Greek mythology), Mars by a shield crossed by a spear, and the remaining classical planets by symbols resembling the modern ones, without the cross-mark at the bottom of the modern versions of the symbols for Mercury and Venus. These cross-marks first appear around the 16th century. According to Maunder, the addition of crosses appears to be "an attempt to give a savour of Christianity to the symbols of the old pagan gods."[28]

-

The symbol for Mercury in late Classical (4th c.) and medieval Byzantine (11th c.) manuscripts[9]

-

The symbol for Venus in late Classical (4th c.) and medieval Byzantine (11th c.) manuscripts[9]

-

The symbol for Mars in late Classical (6th c.) and medieval Byzantine (11th c.) manuscripts[9]

-

The symbol for Jupiter in late Classical (4th c.) and medieval Byzantine (11th c.) manuscripts[9]

The symbols for Uranus were created shortly after its discovery. One symbol, ![]() , invented by J. G. Köhler and refined by Bode, was intended to represent the newly discovered metal platinum; since platinum, commonly called white gold, was found by chemists mixed with iron, the symbol for platinum combines the alchemical symbols for the planetary elements iron, ♂, and gold, ☉.[29][30]

Another symbol,

, invented by J. G. Köhler and refined by Bode, was intended to represent the newly discovered metal platinum; since platinum, commonly called white gold, was found by chemists mixed with iron, the symbol for platinum combines the alchemical symbols for the planetary elements iron, ♂, and gold, ☉.[29][30]

Another symbol, ![]() , was suggested by Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande in 1784. In a letter to William Herschel, Lalande described it as "un globe surmonté par la première lettre de votre nom" ("a globe surmounted by the first letter of your name").[31] Today, Köhler's symbol is more common among astronomers, and Lalande's among astrologers, although it is not uncommon to see each symbol in the other context.[32]

, was suggested by Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande in 1784. In a letter to William Herschel, Lalande described it as "un globe surmonté par la première lettre de votre nom" ("a globe surmounted by the first letter of your name").[31] Today, Köhler's symbol is more common among astronomers, and Lalande's among astrologers, although it is not uncommon to see each symbol in the other context.[32]

Several symbols were proposed for Neptune to accompany the suggested names for the planet. Claiming the right to name his discovery, Urbain Le Verrier originally proposed the name Neptune[33] and the symbol of a trident,[34] while falsely stating that this had been officially approved by the French Bureau des Longitudes.[33] In October, he sought to name the planet Leverrier, after himself, and he had loyal support in this from the observatory director, François Arago,[35] who in turn proposed a new symbol for the planet (![]() ).[36] However, this suggestion met with stiff resistance outside France.[35] French almanacs quickly reintroduced the name Herschel for Uranus, after that planet's discoverer Sir William Herschel, and Leverrier for the new planet.[37] Professor James Pillans of the University of Edinburgh defended the name Janus for the new planet, and proposed a key for its symbol.[34] Meanwhile, German-Russian astronomer Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve presented the name Neptune on December 29, 1846, to the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences.[38] In August 1847, the Bureau des Longitudes announced its decision to follow prevailing astronomical practice and adopt the choice of Neptune, with Arago refraining from participating in this decision.[39]

).[36] However, this suggestion met with stiff resistance outside France.[35] French almanacs quickly reintroduced the name Herschel for Uranus, after that planet's discoverer Sir William Herschel, and Leverrier for the new planet.[37] Professor James Pillans of the University of Edinburgh defended the name Janus for the new planet, and proposed a key for its symbol.[34] Meanwhile, German-Russian astronomer Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve presented the name Neptune on December 29, 1846, to the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences.[38] In August 1847, the Bureau des Longitudes announced its decision to follow prevailing astronomical practice and adopt the choice of Neptune, with Arago refraining from participating in this decision.[39]

The International Astronomical Union discourages the use of these symbols in journal articles, though they do occur.[40] In certain cases where planetary symbols might be used, such as in the headings of tables, the IAU Style Manual permits certain one- and (to disambiguate Mercury and Mars) two-letter abbreviations for the names of the planets.[41]

Planets Planet IAU

abbreviationSymbol Unicode

code pointUnicode

displayRepresents Mercury H, Me

[15][42]U+263F

(dec 9791)☿ Mercury's caduceus, with a cross[9] Venus V

[15][42]U+2640

(dec 9792)♀ Perhaps Venus's necklace or a (copper) hand mirror, with a cross[21][42] Earth E

[15][42]U+1F728

(dec 128808)🜨 the four quadrants of the world, divided by the four rivers descending from Eden[43][a]

[15][21][22]U+2641

(dec 9793)♁ a globus cruciger Mars M, Ma

[15][42]U+2642

(dec 9794)♂ Mars's shield and spear[21][42] Jupiter J

[15][42]U+2643

(dec 9795)♃ the letter Zeta with an abbreviation stroke (for Zeus, the Greek equivalent to the Roman god Jupiter)[9] Saturn S

[15][42]U+2644

(dec 9796)♄ the letters kappa-rho with an abbreviation stroke (for Kronos, the Greek equivalent to the Roman god Saturn), with a cross[9] Uranus U

[29][30]U+26E2

(dec 9954)⛢ symbol of the recently described element platinum, which was invented to provide a symbol for Uranus[29][30]

[22][23][42]U+2645

(dec 9797)♅ a globe surmounted by the letter H (for Herschel, who discovered Uranus)[31]

(more common in older or British literature)Neptune N

[15][23]U+2646

(dec 9798)♆ Neptune's trident

[36][42]U+2BC9

(dec 11209)⯉ a globe surmounted by the letters "L" and "V", (for Le Verrier, who discovered Neptune)[36][42]

(more common in older, especially French, literature)

Symbols for asteroids

[edit]

Following the discovery of Ceres in 1801 by the astronomer and Catholic priest Giuseppe Piazzi, a group of astronomers ratified the name, which Piazzi had proposed. At that time, the sickle was chosen as a symbol of the planet.[46]

The symbol for 2 Pallas, the spear of Pallas Athena, was invented by Baron Franz Xaver von Zach, who organized a group of twenty-four astronomers to search for a planet between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. The symbol was introduced by von Zach in 1802.[47] In a letter to von Zach, discoverer Heinrich Wilhelm Matthäus Olbers (who had discovered and named Pallas) expressed his approval of the proposed symbol, but wished that the handle of the sickle of Ceres had been adorned with a pommel instead of a crossbar, to better differentiate it from the sign of Venus.[47]

-

Symbols for Ceres and Pallas, as rendered in 1802

-

Symbol for Juno, as rendered in 1804 with the available type sorts of an asterisk * and a rotated dagger †

-

Symbol for Vesta, as rendered in 1807

German astronomer Karl Ludwig Harding created the symbol for 3 Juno. Harding, who discovered this asteroid in 1804, proposed the name Juno and the use of a scepter topped with a star as its astronomical symbol.[48]

The symbol for 4 Vesta was invented by German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss. Olbers, having previously discovered and named 2 Pallas, gave Gauss the honor of naming his newest discovery. Gauss decided to name the new asteroid for the goddess Vesta, and also designed the symbol (![]() ): the altar of the goddess, with the sacred fire burning on it.[49][50][51] Other contemporaneous writers use a more elaborate symbol (

): the altar of the goddess, with the sacred fire burning on it.[49][50][51] Other contemporaneous writers use a more elaborate symbol (![]()

![]() ) instead.[52][53]

) instead.[52][53]

Karl Ludwig Hencke, a German amateur astronomer, discovered the next two asteroids, 5 Astraea (in 1845) and 6 Hebe (in 1847). Hencke requested that the symbol for 5 Astraea be an upside-down anchor;[54] however, a weighing scale was sometimes used instead.[16][55] Gauss named 6 Hebe at Hencke's request, and chose a wineglass as the symbol.[56][57]

As more new asteroids were discovered, astronomers continued to assign symbols to them. Thus, 7 Iris (discovered 1847) had for its symbol a rainbow with a star;[58] 8 Flora (discovered 1847), a flower;[58] 9 Metis (discovered 1848), an eye with a star;[59] 10 Hygiea (discovered 1849), an upright snake with a star on its head;[60] 11 Parthenope (discovered 1850), a standing fish with a star;[60] 12 Victoria (discovered 1850), a star topped with a branch of laurel;[61] 13 Egeria (discovered 1850), a buckler;[62] 14 Irene (discovered 1851), a dove carrying an olive branch with a star on its head;[63] 15 Eunomia (discovered 1851), a heart topped with a star;[64] 16 Psyche (discovered 1852), a butterfly wing with a star;[65] 17 Thetis (discovered 1852), a dolphin with a star;[66] 18 Melpomene (discovered 1852), a dagger over a star;[67] and 19 Fortuna (discovered 1852), a star over Fortuna's wheel.[67][b]

In most cases the discovery reports only describe the symbols and do not draw them; from Hygiea onward, there are significant glyph variants as well as a significant delay between the discovery and the symbols having been communicated to the astronomical community as a whole.[70][71] Consequently, astronomical publications were not always complete.[45] The discovery reports for Melpomene[72] and Fortuna[73] do not even describe the symbols, which only appear in a later reference work by the discoverer;[67] the symbols are drawn in the reports for Astraea,[54] Hebe,[56] and Thetis.[66] Benjamin Apthorp Gould criticised the symbols in 1852 as being often inefficient at suggesting the bodies they represented and difficult to draw, and pointed out that the symbol that had been described for Irene had to his knowledge never actually been drawn.[74] The same year, John Russell Hind expressed the contrary view that the symbols were easier to remember than the numbers, but also admitted that the names were more commonly used than either the numbers or the symbols.[67]

The last edition of the Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch (BAJ, Berlin Astronomical Yearbook) to use asteroid symbols was for the year 1853, published in 1850: although it includes eleven asteroids up to Parthenope, it only includes symbols for the first nine (up to Metis), noting that the symbols for Hygiea and Parthenope had not yet been made definitively known.[70] The last edition of the British The Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris to include asteroid ephemerides was that for 1855, published in 1852: despite fifteen asteroids being known (up to Eunomia), symbols are only included for the first nine.[75]

Johann Franz Encke made a major change in the BAJ for the year 1854, published in 1851. He introduced encircled numbers instead of symbols, although his numbering began with Astraea, the first four asteroids continuing to be denoted by their traditional symbols.[16] This symbolic innovation was adopted very quickly by the astronomical community. The following year (1852), Astraea's number was bumped up to 5, but Ceres through Vesta were not listed by their numbers until the 1867 edition.[16] The Astronomical Journal edited by Gould adopted the symbolism in this form, with Ceres at 1 and Astraea at 5.[74] This form had previously been proposed in an 1850 letter by Heinrich Christian Schumacher to Gauss.[71] The circle later became a pair of parentheses, which were easier to typeset,[45] and the parentheses were sometimes omitted altogether over the next few decades.[16] Thus the iconic asteroid symbols fell out of use; reference works continued giving them for the next few decades, though they often noted them as being obsolete.[45]

A few asteroids were given symbols by their discoverers after the encircled-number notation became widespread. 26 Proserpina (discovered 1853), 28 Bellona (discovered 1854), 35 Leukothea (discovered 1855), and 37 Fides (discovered 1855), all discovered by German astronomer Robert Luther, were assigned, respectively, a pomegranate with a star inside;[76] a whip and spear;[77] an antique lighthouse;[78] and a cross.[79] These symbols were drawn in the discovery reports. 29 Amphitrite was named and assigned a shell for its symbol by George Bishop, the owner of the observatory where astronomer Albert Marth discovered it in 1854, though the symbol was not drawn in the discovery report.[80]

All these symbols are rare or obsolete in modern astronomy, though NASA has used Ceres' symbol when describing the dwarf planets,[81] and Psyche's symbol may have influenced the design of the insignia for the Psyche mission.[45] The major use of symbols for minor planets today is by astrologers, who have invented symbols for many more objects, though they sometimes use symbols that differ from the historical symbols for the same bodies.[82]

The symbol for 99942 Apophis, a near-Earth asteroid discovered in 2004 that attracted interest when initial observations suggested a significant probability of an Earth impact in 2029 (a possibility since eliminated), is much later. It was designed by Denis Moskowitz, who also designed many of the dwarf-planet symbols, at a time when asteroid symbols had become extremely rare in astronomy. Nonetheless, its inclusion of a star is meant to recall the 19th-century asteroid symbols.[83]

Table

[edit]| Asteroid | Symbol | Unicode code point |

Unicode display |

Represents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ceres | [16][22][42] |

U+26B3 (dec 9907) |

⚳ | A scythe.[42] In some fonts, the symbol for Saturn is the inverse. |

| 2 Pallas | [47] |

U+26B4 (dec 9908) |

⚴ | A spear.[47][55] In modern renditions, the spearhead has a broader or narrower diamond shape. In 1802, it was given a cordate leaf shape. A variation has a triangular head, conflating it with the alchemical symbol for sulfur. |

[47] | ||||

| 3 Juno | [48][85] |

U+26B5 (dec 9909) |

⚵ | a scepter topped with a star[48] |

[42][86] | ||||

| 4 Vesta | [49] |

U+1F777 (dec 128887) |

| The temple hearth with the sacred fire of Vesta. The original form was a box with what looks like the horns of Aries on top.[49][51] |

[16][55][86] |

An early elaborate form is an altar surmounted with a censer holding the sacred fire.[49][51] | |||

[51] |

U+26B6 (dec 9910) |

⚶ | The modern V-shaped form dates from astrological use in the 1970s; it is an abbreviation of the above.[49][51] | |

| 5 Astraea | [54][55] |

U+1F778 (dec 128888) |

| an inverted anchor[54][87] |

[88] |

U+2696 (dec 9878) |

⚖ | a weighing scale[42][55] | |

| 6 Hebe | [56][89][90] |

U+1CEC0 (dec 118464) |

| A wineglass. Originally typeset as a triangle ∇ set on a base ⊥.[56] |

[16][42][55] | ||||

| 7 Iris | [16][42] |

U+1CEC1 (dec 118465) |

| a rainbow with a star inside it[58] |

[58][67] | ||||

| 8 Flora | [16][55] |

U+1CEC2 (dec 118466) |

| a flower[58] |

| 9 Metis | [16][42][55] |

U+1CEC3 (dec 118467) |

| an eye with a star above it[59] |

| 10 Hygiea | [60][67] |

U+1F779 (dec 128889) |

| a serpent with a star (from the Bowl of Hygiea U+1F54F |

[16][55] |

U+2695 (dec 9877) |

⚕ | a Rod of Asclepius. Cf. the modern astrological symbol U+2BDA | |

| 11 Parthenope | [16][60] |

U+1CEC4 (dec 118468) |

| a fish with a star. This is the original symbol from the brief period when this asteroid was known and astronomers were still using iconic symbols.[60] |

[88] |

U+1F77A (dec 128890) |

| a lyre. This symbol only appears in later 19th-century reference works that appeared when iconic symbols for asteroids had already become obsolete.[45] | |

| 12 Victoria | [16][55] |

U+1CEC5 (dec 118469) |

| a star with a branch of laurel[61] |

[91] | ||||

| 13 Egeria | [91] |

U+1CEC6 (dec 118470) |

| a buckler[62] |

[67] | ||||

| 14 Irene | [88] |

U+1CEC7 (dec 118471) |

| a dove carrying an olive-branch in its mouth and a star on its head[63] |

| 15 Eunomia | [16][55] |

U+1CEC8 (dec 118472) |

| a heart with a star on top[64] |

| 16 Psyche | [67] |

U+1CEC9 (dec 118473) |

| a butterfly's wing and a star[65] |

| 17 Thetis | [66] |

U+1CECA (dec 118474) |

| a dolphin and a star[66] |

| 18 Melpomene | [67] |

U+1CECB (dec 118475) |

| a dagger over a star[67] |

| 19 Fortuna | [67] |

U+1CECC (dec 118476) |

| a star over a wheel[67] |

| 26 Proserpina | [76] |

U+1CECD (dec 118477) |

| a pomegranate with a star inside it[76] |

| 28 Bellona | [77] |

U+1CECE (dec 118478) |

| Bellona's whip / morning star and spear[77] |

| 29 Amphitrite | [91] |

U+1CECF (dec 118479) |

| a "shell".[80] There is no mention of a star in the original description, but the only 19th-century drawing of the symbol includes one.[45] |

| 35 Leukothea | [78] |

U+1CED0 (dec 118480) |

| a pharos (ancient lighthouse)[78] |

| 37 Fides | [79] |

U+271D (dec 10013) |

✝ | a Latin cross[79][91] |

| 99942 Apophis | [83] |

— | — | a stylised depiction of the Egyptian god Apep, with a star[83] |

Symbols for trans-Neptunian objects

[edit]Pluto's name and symbol were announced by the discoverers on May 1, 1930.[92] The symbol, a monogram of the letters PL, could be interpreted to stand for Pluto or for Percival Lowell, the astronomer who initiated Lowell Observatory's search for a planet beyond the orbit of Neptune. Pluto has an alternative symbol consisting of an orb over Pluto's bident: it is more common in astrology than astronomy, and was popularised by the astrologer Paul Clancy,[93] but has been used by NASA to refer to Pluto as a dwarf planet.[81] There are a few other astrological symbols for Pluto that are used locally.[93] Pluto also had the IAU abbreviation P when it was considered the ninth planet.[41]

The other large trans-Neptunian objects were only discovered around the dawn of the 21st century. They were not generally thought to be planets on their discovery, and planetary symbols had in any case mostly fallen out of use among astronomers by then. Denis Moskowitz, a software engineer in Massachusetts,[94] proposed astronomical symbols for the dwarf planets Quaoar, Sedna, Orcus, Haumea, Eris, Makemake, and Gonggong.[95][94] These symbols are somewhat standard among astrologers (e.g. in the program Astrolog),[96] which is where planetary symbols are most used today. Moskowitz has also proposed symbols for Varuna, Ixion, and Salacia, and others have done so for additional TNOs, but there is little consistency between sources.[95]

NASA has used Moskowitz's symbols for Haumea, Makemake, and Eris in an astronomical context, and Unicode labels the symbols for Haumea, Makemake, Gonggong, Quaoar, and Orcus (added to Unicode in 2022) as "astronomy symbols".[94] Therefore, symbols mentioned in the Unicode proposal for Haumea, Makemake, Gonggong, Quaoar, and Orcus have been shown below to fill out the list of named TNOs down to 600 km diameter, even though not all of them are actually attested in astronomical use. (Grundy et al. suggest 600 to 700 km diameter as a speculative upper limit for a trans-Neptunian object to retain substantial pore space.)[97]

| Object | Symbol | Unicode code point |

Unicode display |

Represents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20000 Varuna | [95] |

— | — | based on the initial Devanagari letter of its name, व va, and the snake-lasso Varuna is said to carry[95] |

| 28978 Ixion | [95] |

— | — | based on the letters I and X for Ixion, plus the rim of the wheel that Ixion was bound to in Hades[95] |

[95] |

— | — | a variant, substituting a Greek Ξ (capital xi) for the X[95] | |

| 50000 Quaoar | [95] |

U+1F77E (dec 128894) |

🝾 | a Q for Quaoar with the tail fashioned as a canoe, stylised to resemble the angular rock art of the Tongva[95] |

| 90377 Sedna | [95] |

U+2BF2 (dec 11250) |

⯲ | a monogram of the Inuktitut syllabics ᓴ sa and ᓐ n, as Sedna's Inuit name is ᓴᓐᓇ Sanna[98] |

| 90482 Orcus | [95] |

U+1F77F (dec 128895) |

🝿 | an O-R monogram for Orcus, stylised to resemble a skull and an orca's grin[95] |

| 120347 Salacia | [99] |

— | — | a stylized hippocamp (mer-horse) incorporating a Latin S (top) or a Greek sigma σ (bottom)[95] |

[95] | ||||

| 134340 Pluto | [15] |

U+2647 (dec 9799) |

♇ | a P-L monogram for Pluto and Percival Lowell |

[81] |

U+2BD3 (dec 11219) |

⯓ | a cap or planetary orb over Pluto's bident | |

| 136108 Haumea | [81] |

U+1F77B (dec 128891) |

🝻 | conflation of Hawaiian petroglyphs for woman and birth, as Haumea was the goddess of both[95] |

| 136199 Eris | [81] |

U+2BF0 (dec 11248) |

⯰ | the Hand of Eris, a traditional symbol from Discordianism (a religion worshipping the goddess Eris)[51] |

| 136472 Makemake | [81] |

U+1F77C (dec 128892) |

🝼 | engraved face of the Rapa Nui god Makemake, also resembling an M[95] |

| 174567 Varda | [95] |

U+2748 (dec 10056) |

❈ | a gleaming star, as Varda was the creator of the stars |

| 225088 Gonggong | [95] |

U+1F77D (dec 128893) |

🝽 | Chinese character 共 gòng (the first character in Gonggong's name), combined with a snake's tail[95] |

| 229762 Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà | [95] |

— | — | an aardvark, representing the beautiful aardvark girl Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà[95] |

Symbols for zodiac and other constellations

[edit]

The zodiac symbols have several astronomical interpretations. Depending on context, a zodiac symbol may denote either a constellation, or a point or interval on the ecliptic plane.

Lists of astronomical phenomena published by almanacs sometimes included conjunctions of stars and planets or the Moon; rather than print the full name of the star, a Greek letter and the symbol for the constellation of the star was sometimes used instead.[100][101] The ecliptic was sometimes divided into 12 signs, each subdivided into 30 degrees,[102][103] and the sign component of ecliptic longitude was expressed either with a number from 0 to 11.[104] or with the corresponding zodiacal symbol.[103]

In modern astronomical writing, all the constellations, including the 12 of the zodiac, have dedicated three-letter abbreviations, which specifically refer to constellations rather than signs.[105] The zodiac symbols are also sometimes used to represent points on the ecliptic, particularly the solstices and equinoxes. Each symbol is taken to represent the "first point" of each sign, rather than the place in the visible constellation where the alignment is observed.[106][107] Thus, ♈︎ the symbol for Aries, represents the March equinox;[c] ♋︎, for Cancer, the June solstice;[d] ♎︎, for Libra, the September equinox;[e] and ♑︎, for Capricorn, the December solstice.[f]

Although the use of astrological sign symbols is rare, the particular symbol ♈︎ for Aries, is an exception; it is commonly used in modern astronomy to represent the location of the (slowly) moving reference point for the ecliptic and equatorial celestial coordinate systems.

Zodiacal symbols Constellation IAU

abbreviationNumber Astrological

locationSymbol Translation Unicode

code pointUnicode

displayAries Ari[41] 0 0°

[103][5]ram[108] U+2648

(dec 9800)♈︎ Taurus Tau[41] 1 30°

[103][5]bull[108] U+2649

(dec 9801)♉︎ Gemini Gem[41] 2 60°

[103][5]twinned[108] U+264A

(dec 9802)♊︎ Cancer Cnc[41]

[103][5]3 90°

[103][5]crab[108] U+264B

(dec 9803)♋︎ Leo Leo[41] 4 120°

[103][5]lion[108] U+264C

(dec 9804)♌︎ Virgo Vir[41] 5 150°

[103][5]maiden[108] U+264D

(dec 9805)♍︎ Libra Lib[41] 6 180°

[103][5]scales[108] U+264E

(dec 9806)♎︎ Scorpio Sco[41] 7 210°

[103][5]scorpion[108] U+264F

(dec 9807)♏︎ Sagittarius Sgr[41] 8 240°

[103][5]archer[108] U+2650

(dec 9808)♐︎ Capricorn Cap[41] 9 270°

[103][5]having a goat's horns[108] U+2651

(dec 9809)♑︎ Aquarius Aqr[41] 10 300°

[103][5]water-carrier[108] U+2652

(dec 9810)♒︎ Pisces Psc[41] 11 330°

[103][5]fishes[108] U+2653

(dec 9811)♓︎

Ophiuchus has been proposed as a thirteenth sign of the zodiac by astrologer Walter Berg in 1995, who gave it a symbol that has become popular in Japan.[citation needed]

Constellation IAU

abbreviationSymbol Translation Unicode

code pointUnicode

displayOphiuchus Oph[41]

[5]the Serpent-holder[108] U+26CE

(dec 9934)⛎︎

None of the constellations have official symbols. However, occasional symbols for the modern constellations, as well as older ones that occur in modern nomenclature, have appeared in publication. The symbols below were devised by Denis Moskowitz (except those for the 13 constellations already listed above).[99][109]

- Andromeda

- Antlia

- Apus

- Aquarius

- Aquila

- Ara

- Argo Navis

- Aries

- Auriga

- Boötes

- Caelum

- Camelopardalis

- Cancer

- Canes Venatici

- Canis Major

- Canis Minor

- Capricornus

- Cassiopeia

- Centaurus

- Cepheus

- Cetus

- Chamaeleon

- Circinus

- Columba

- Coma Berenices

- Corona Australis

- Corona Borealis

- Corvus

- Crater

- Crux

- Cygnus

- Delphinus

- Dorado

- Draco

- Equuleus

- Eridanus

- Fornax

- Gemini

- Grus

- Hercules

- Horologium

- Hydra

- Hydrus

- Indus

- Lacerta

- Leo

- Leo Minor

- Lepus

- Libra

- Lupus

- Lynx

- Lyra

- Mensa

- Microscopium

- Monoceros

- Musca

- Norma

- Octans

- Ophiuchus

- Orion

- Pavo

- Pegasus

- Perseus

- Phoenix

- Pictor

- Pisces

- Piscis Austrinus

- Pyxis

- Quadrans Muralis

- Reticulum

- Sagitta

- Sagittarius

- Scorpius

- Sculptor

- Scutum

- Serpens

- Sextans

- Taurus

- Telescopium

- Triangulum

- Triangulum Australe

- Tucana

- Ursa Major

- Ursa Minor

- Virgo

- Volans

- Vulpecula

Other symbols

[edit]Symbols for aspects and nodes appear in medieval texts, although medieval and modern usage of the node symbols differ; the modern ascending node symbol (☊) formerly stood for the descending node, and the modern descending node symbol (☋) was used for the ascending node.[3] In describing the Keplerian elements of an orbit, ☊ is sometimes used to denote the ecliptic longitude of the ascending node, although it is more common to use Ω (capital omega, and inverted ℧), which were originally typographical substitutes for the astronomical symbols.[110]

The symbols for aspects first appear in Byzantine codices.[3] Of the symbols for the five Ptolemaic aspects, only the three displayed here — for conjunction, opposition, and quadrature — are used in astronomy.[111]

Symbols for a comet (☄) and a star (![]() ) have been used in published astronomical observations of comets. In tables of these observations, ☄ stood for the comet being discussed and

) have been used in published astronomical observations of comets. In tables of these observations, ☄ stood for the comet being discussed and ![]() for the star of comparison relative to which measurements of the comet's position were made.[112]

for the star of comparison relative to which measurements of the comet's position were made.[112]

Other symbols Referent Symbol Unicode

code pointUnicode

displayascending node

[15][22]U+260A

(dec 9738)☊ descending node

[15][22]U+260B

(dec 9739)☋ conjunction

[22][23]U+260C

(dec 9740)☌ opposition

[22][23]U+260D

(dec 9741)☍ occultation

[113]U+1F775

(dec 128885)🝵 a lunar eclipse,

or any body in the

shadow of another[114]

[113]U+1F776

(dec 128886)🝶 quadrature

[22][23]U+25A1, U+25FB

(dec 9633, 9723)□ , ◻ comet

[22][91][112]U+2604

(dec 9732)☄ star

[22][91][112](various)[g] ✶ 🞶 ★ planetary rings

(rare)

[115]U+1FA90+FE0E

(dec 129680)🪐︎

Meteor showers also have limited use of astronomical symbols in the literature, designed by Denis Moskowitz. They are based on the parent constellation symbols, with letters included to disambiguate the Aquariids and Taurids.[99][83]

For planetary transits of Mercury and Venus, Moskowitz proposed overlaying the respective planetary symbol on that of the Sun, extending the crossbar into an arrow: ![]() (Mercury),

(Mercury), ![]() (Venus). This also has some limited use.[83]

(Venus). This also has some limited use.[83]

Limited use can also be found of Moskowitz's symbol for Halley's Comet, ![]() : it is simply the standard comet symbol with an H.[83]

: it is simply the standard comet symbol with an H.[83]

See also

[edit]- Astrological symbols

- Alchemical symbols

- List of common astronomy symbols

- Maya calendar for the logograms used in Maya astronomy

- Solar symbol

- Zodiac

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ This symbol has been reinterpretated as the four continents (north: Europe, east: Asia, south: Africa, west: America), and in such cases may be modified to

. A less common variant is

. A less common variant is  , now obsolete.[44]

, now obsolete.[44]

- ^ John Brocklesby's Elements of Astronomy (1855 edition) contains unusual symbols for 19 Fortuna (similar to Astraea's inverted anchor) and 20 Massalia (an anchor) not attested anywhere else on p. 14, but they do not appear in the detailed asteroid profiles on p. 235[68] and were removed from the 1857 edition, suggesting that they were mistakes.[69]

- ^ The March equinox defines the astrological sign of Aries, and is also used as the point of origin for most modern celestial coordinate systems. But at present, the equinox actually occurs in the western part of the astronomical constellation Pisces, near its southern border, and is slowly transitioning into the constellation Aquarius.

- ^ The June solstice is aligned with the sign of Cancer, but occurs very nearly on the modern border between Gemini and Taurus.

- ^ The September equinox is aligned with the sign of Libra, but occurs in western Virgo.

- ^ The December solstice is aligned with the sign Capricorn, but occurs very nearly on top of the modern border between Sagittarius and Ophiuchus.

- ^ There is no particular Unicode character designated as a standard astronomical symbol for a star. Possibilities include ✶ U+2736, ★ U+2605, or a six-pointed asterisk such as 🞶 U+1F7B6.

References

[edit]- ^ Encke, Johann Franz (1850). Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch für 1853 [The Berlin Astronomical Almanac for 1853] (in German). Berlin. p. VIII.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Neugebauer, Otto (1975). A History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy. pp. 788–789. ISBN 978-0-387-06995-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Neugebauer, Otto; van Hoesen, H.B. (1987). Greek Horoscopes. American Philosophical Society. pp. 1, 159, 163. ISBN 978-0-8357-0314-7.

- ^ Pasko, Wesley Washington (1894). American dictionary of printing and bookmaking. H. Lockwood. p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Miscellaneous Symbols" (PDF). unicode.org. The Unicode Consortium. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ "Miscellaneous Symbols and Arrows" (PDF). unicode.org. The Unicode Consortium. 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 2, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ "Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs" (PDF). unicode.org. The Unicode Consortium. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ "Alchemical Symbols" (PDF). unicode.org. The Unicode Consortium. 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jones, Alexander (1999). Astronomical Papyri from Oxyrhynchus. American Philosophical Society. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-87169-233-7.

- ^ Green, Simon F.; Jones, Mark H.; Burnell, S. Jocelyn (2004). An Introduction to the Sun and Stars. Cambridge University Press. p. 8.

- ^ Goswami, Aruna (2010). Principles and Perspectives in Cosmochemistry: Lecture notes of the Kodai School on Synthesis of Elements in Stars held at Kodaikanal Observatory, India, April 29 – May 13, 2008. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Gray, David F. (2005). The Observation and Analysis of Stellar Photospheres. Cambridge University Press. p. 505.

- ^ Salaris, Maurizio; Cassisi, Santi (2005). Evolution of Stars and Stellar Populations. John Wiley and Sons. p. 351.

- ^ Tielens, A.G.G.M. (2005). The Physics and Chemistry of the Interstellar Medium. Cambridge University Press. p. xi.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cox, Arthur (2001). Allen's Astrophysical Quantities. Springer. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-387-95189-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hilton, James L. (June 14, 2011). "When did the Asteroids become Minor Planets?". Archived from the original on August 10, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Frey, A. (1857). Nouveau manuel complet de typographie contenant les principes théoriques et pratiques de cet art (in French). Librairie encyclopédique de Roret. p. 379.

- ^ Éphémérides des mouvemens célestes [Ephemeridies of Celestial Positions] (in French). 1774. p. xxxiv.

- ^ The American Practical Navigator, chapter 13, 'Navigational Astronomy'

- ^ Text display is forced by appending U+FE0E to the character. Emojis are forced by appending U+FE0F.

- ^ a b c d The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Vol. 22. C. Knight. 1842. p. 197.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n The Encyclopedia Americana: A library of universal knowledge. Vol. 26. Encyclopedia Americana Corp. 1920. pp. 162–163. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Putnam, Edmund Whitman (1914). The essence of astronomy: things every one should know about the sun, moon, and stars. G.P. Putnam's sons. p. 197.

- ^ a b c d Almanach de Gotha. Vol. 158. 1852. p. ii.

- ^ a b c d Almanach Hachette. Hachette. 1908. p. 8.

- ^ a b Jim Maynard, Celestial Calendars

- ^ "Bianchini's planisphere". Florence, Italy: Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza [Institute and Museum of the History of Science]. Archived from the original on February 27, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Maunder, A.S.D. (1934). "The origin of the symbols of the planets". The Observatory. Vol. 57. pp. 238–247. Bibcode:1934Obs....57..238M.

- ^ a b c Bode, J.E. (1784). Von dem neu entdeckten Planeten [On the newly discovered planets]. Beim Verfaszer. pp. 95–96. Bibcode:1784vdne.book.....B.

- ^ a b c Gould, B. A. (1850). Report on the history of the discovery of Neptune. Smithsonian Institution. p. 5.

- ^ a b Herschel, Francisca (1917). "The meaning of the symbol H+o for the planet Uranus". The Observatory. Vol. 40. p. 306. Bibcode:1917Obs....40..306H.

- ^ Anderson, Deborah; Iancu, Laurențiu; Sargent, Murray (August 14, 2019). "Proposal to Encode the Astronomical Symbol for Uranus" (PDF). Unicode. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Littmann, Mark; E.M., Standish (2004). Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System. Courier Dover Publications. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-486-43602-9.

- ^ a b Pillans, James (1847). "Ueber den Namen des neuen Planeten" [On the names of the new planets]. Astronomische Nachrichten. 25 (26): 389–392. Bibcode:1847AN.....25..389.. doi:10.1002/asna.18470252602.

- ^ a b Baum, Richard; Sheehan, William (2003). In Search of Planet Vulcan: The Ghost in Newton's Clockwork Universe. Basic Books. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-7382-0889-3.

- ^ a b c Schumacher, H.C. (1846). "Name des Neuen Planeten" [Name for the new planet]. Astronomische Nachrichten (in German). 25 (6): 81–82. Bibcode:1846AN.....25...81L. doi:10.1002/asna.18470250603.

- ^ Gingerich, Owen (1958). "The Naming of Uranus and Neptune". Leaflet of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Leaflets. 8 (352). Astronomical Society of the Pacific: 9–15. Bibcode:1958ASPL....8....9G.

- ^ Hind, J.R. (1847). "Second report of proceedings in the Cambridge Observatory relating to the new Planet (Neptune)". Astronomische Nachrichten. 25 (21): 309–314. Bibcode:1847AN.....25..309.. doi:10.1002/asna.18470252102. Archived from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ Connaissance des temps: ou des mouvementes célestes, à l'usage des astronomes (in French). France: Bureau des Longitudes. 1847. p. unnumbered front matter.

- ^ E.g. p. 10, fig. 3 in Chen & Kipping (2017) Probabilistic Forecasting of the Masses and Radii of Other Worlds Archived September 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The Astrophysical Journal, 834: 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o The IAU Style Manual (PDF). The International Astrophysical Union. 1989. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Mattison, Hiram (1872). High-School Astronomy. Sheldon & Co. pp. 32–36.

- ^ Unicode characters with a similar shape:

:U+2295 ⊕ CIRCLED PLUS;

:U+2A01 ⨁ N-ARY CIRCLED PLUS OPERATOR; U+1F310 🌐︎ GLOBE WITH MERIDIANS - ^ "Solar System", in The English Cyclopaedia of Arts and Sciences, vol. VII-VIII, 1861

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bala, Gavin Jared; Miller, Kirk (September 18, 2023). "Unicode request for historical asteroid symbols" (PDF). unicode.org. Unicode. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Bode, J.E., ed. (1801). Berliner astronomisches Jahrbuch führ das Jahr 1804 [The Berlin Astronomical Yearbook for 1804]. pp. 97–98. Archived from the original on December 14, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e von Zach, Franz Xaver (1802). "Monatliche correspondenz zur beförderung der erd- und himmels-kunde" [Monthly correspondence for furthering Earth and Space Sciences [journal]]. pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b c von Zach, Franz Xaver (1804). Monatliche correspondenz zur beförderung der erd- und himmels-kunde [Monthly correspondence for furthering Earth and Space Sciences [journal]] (in German). Vol. 10. p. 471.

- ^ a b c d e von Zach, Franz Xaver (1807). Monatliche correspondenz zur beförderung der erd- und himmels-kunde [Monthly correspondence for furthering Earth and Space Sciences [journal]] (in German). Vol. 15. p. 507.

- ^ Carlini, Francesco (1808). Effemeridi astronomiche di Milano per l'anno 1809 [Astronomical Ephemeridies of Milan for the Year 1809] (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e f Faulks, David (May 9, 2006). "Proposal to add some Western Astrology Symbols to the UCS" (PDF). p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

In general, only the signs for Vesta have enough variance to be regarded as different designs. However, all of these Vesta symbols ... are differing designs for "the hearth and flame of the temple of the Goddess Vesta" in Rome, and can thus be regarded as extreme variants of a single symbol.

- ^ Annuaire pour l'an 1808 [Almanac for the Year 1808] (in French). France: Bureau des longitudes. 1807. p. 5.

- ^ Canovai, Stanislao; del-Ricco, Gaetano (1810). Elementi di fisica matematica [Elements of Mathematical Physics] (in Italian). p. 149.

- ^ a b c d

Bericht über die zur Bekanntmachung geeigneten Verhandlungen der Königl. Preuss. Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin; Königlich Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. 1845. p. 406.

Der Planet hat mit Einwilligung des Entdeckers den Namen Astraea erhalten, und sein Zeichen wird nach dem Wunsche des Hr. Hencke ein umgekehrter Anker [symbol pictured] sein.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-0-354-06174-2.

- ^ a b c d Wöchentliche Unterhaltungen für Dilettanten und Freunde der Astronomie, Geographie und Witterungskunde [Weekly entertainments for Enthusiasts and Friends of Astronomy, Geography, and Meteorology]. 1847. p. 315.

- ^ Steger, Franz (1847). Ergänzungs-conversationslexikon [Supplementary Conversational Lexicon] (in German). Vol. 3. p. 442.

Hofrath Gauß gab auf Hencke's Ansuchen diesem neuen Planetoiden den Namen Hebe mit dem Zeichen (ein Weinglas).

- ^ a b c d e "Report of the Council to the Twenty-eighth Annual General Meeting". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 8 (4): 82. 1848. Bibcode:1848MNRAS...8...82.. doi:10.1093/mnras/8.4.57.

The symbol adopted for [Iris] is a semicircle to represent the rainbow, with an interior star and a base line for the horizon. ... The symbol adopted for [Flora's] designation is the figure of a flower.

- ^ a b

"Extract of a letter from Mr. Graham". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 8: 147. 1848.

I trust, therefore, that astronomers will adopt this name [viz. Metis], with an eye and star for symbol.

- ^ a b c d e f de Gasparis, Annibale (1850). "Letter to Mr. Hind, from Professor Annibale de Gasparis". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 11: 1. Bibcode:1850MNRAS..11....1D. doi:10.1093/mnras/11.1.1a.

The symbol of Hygeia is a serpent (like a Greek ζ) crowned with a star. That of Parthenope is a fish crowned with a star.

- ^ a b Hind, J.R. (1850). "Letter from Mr. Hind". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 11: 2. Bibcode:1850MNRAS..11....2H. doi:10.1093/mnras/11.1.2.

I have called the new planet Victoria, for which I have devised, as a symbol, a star and laurel branch, emblematic of the goddess of Victory.

- ^ a b "Correspondance". Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences. 32. France: Académie des Sciences: 224. 1851.

M. de Gasparis adresse ses remerciments à l'Académie, qui lui a décerné, dans la séance solennelle du 16 décembre 1850, deux des médailles de la fondation Lalande, pour la découverte des planètes Hygie, Parthénope et Egérie. M. d Gasparis annonce qu'il a choisi, pour symbole de cette dernière planète, la figure d'un bouclier.

- ^ a b Hind, J.R. (1851). "On the discovery of a fourth new planet, at Mr. Bishop's observatory, Regent's Park". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 11 (8): 171. doi:10.1093/mnras/11.8.170a.

Sir John Herschel, who kindly undertook the selection of a name for this, the fourteenth member of the ultra-zodiacal group, has suggested Irene as one suitable to the present time, the symbol to be a dove carrying an olive-branch with a star on the head; and since the announcement of this name, I have been gratified in receiving from all quarters the most unqualified expressions of approbation.

- ^ a b de Gasparis, Annibale (1851). "Beobachtungen und Elemente der Eunomia" [Observations and elements for Eunomia]. Astronomische Nachrichten (in French). 33 (11): 174. Bibcode:1851AN.....33..173D. doi:10.1002/asna.18520331107.

J'ai proposé le nom Eunomia pour la nouvelle planète. Le symbole serait un coeur surmonté d'une étoile.

- ^ a b Sonntag, A. (1852). "Elemente und Ephemeride der Psyche" [Elements and ephemeridies for Psyche]. Astronomische Nachrichten (in German). 34 (20): 283–286. Bibcode:1852AN.....34..283.. doi:10.1002/asna.18520342010.

(in a footnote) Herr Professor de Gasparis schreibt mir, in Bezug auf den von ihm März 17 entdeckten neuen Planeten: "J'ai proposé, avec l'approbation de Mr. Hind, le nom de Psyché pour la nouvelle planète, ayant pour symbole une aile de papillon surmontée d'une étoile."

- ^ a b c d Luther, R. (1852). "Beobachtungen der Thetis auf der Bilker Sternwarte" [Observations of Thetis at the Bilker observatory]. Astronomische Nachrichten (in German). 34 (16): 243–244. doi:10.1002/asna.18520341606.

Herr Director Argelander in Bonn, welcher der hiesigen Sternwarte schon seit längerer Zeit seinen Schutz und Beistand zu Theil werden lässt, hat die Entdeckung des April-Planeten zuerst constatirt und mir bei dieser Gelegenheit dafür den Namen Thetis und das Zeichen [symbol pictured] vorgeschlagen, wodurch der der silberfüssigen Göttinn geheiligte Delphin angedeutet wird. Indem ich mich hiermit einverstanden erkläre, ersuche ich die sämmtlichen Herren Astronomen, diesen Namen und dieses Zeichen annehmen und beibehalten zu wollen.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hind, J.R. (1852). An Astronomical Vocabulary. pp. v–vi.

- ^ Brocklesby, John (1855). Elements of Astronomy. New York: Farmer, Brace & Co. pp. 14–15, 235.

- ^ Brocklesby, John (1857). Elements of Astronomy. New York: Farmer, Brace & Co. pp. 14–15, 235.

- ^ a b Johann Franz Encke, ed. (1850). Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch für 1853. p. viii.

Die Zeichen von Hygiea und Parthenope sind noch nicht so definitiv bekannt gemacht, dass sie hier aufgeführt werden könnten. Die neu endeckte Victoria kommt in diesem Bande noch nicht vor.

- ^ a b Gauss, Carl Friedrich; Schumacher, Heinrich Christian (1865). Peters, Christian Friedrich August (ed.). Briefwechsel zwischen C. F. Gauss und H. C. Schumacher (in German). p. 115. Archived from the original on October 7, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

Wenn noch mehrere von dieser Planetenfamilie entdeckt werden, so möchte es am Ende schwer halten, neue geeignete Zeichen aufzufinden, auch kann man doch eigentlich nicht von einem Atronomen verlangen, dass er Blumen- und Figurenzeichner seyn soll. Ich glaube es wäre weit bequemer, alle mit einem Kreise, der die Ordnungszahl ihrer Endeckung enthält, zu bezeichnen: Ceres mit ① Victoria mit ⑫ u. s. w. Man kommt dann nie in Verlegenheit. Es mögen so viele, wie man will, entdeckt werden, das Zeichen ist im voraus bestimmt. Alle diese Zeichen sind leicht zu schreiben, und sehen im Drucke gut aus, auch zeigt der letzte immer wie viele von der Brut da sind. Ich würde, wenn ich nicht einen grossen Abscheu vor allen nicht absolut nothwendigen Neuerungen hätte, den Vorschlag in den A. N. [Astronomische Nachrichten] machen.

- ^ Hind, J. R. (1852). "Melpomene". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 12 (8): 194–199. doi:10.1093/mnras/12.8.194.

- ^ Hind, J. R. (1852). "Fortuna". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 12 (8): 192–194. doi:10.1093/mnras/12.8.192.

- ^ a b Gould, B. A. (1852). "On the symbolic notation of the asteroids". The Astronomical Journal. 2 (34): 80. Bibcode:1852AJ......2...80G. doi:10.1086/100212.

- ^ The Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris for the Year 1855. 1852. p. xiv.

- ^ a b c Luther, R. (1853). "Beobachtungen des neuesten Planeten auf der Bilker Sternwarte". Astronomische Nachrichten. 36 (24): 349–350. Bibcode:1853AN.....36Q.349.. doi:10.1002/asna.18530362403.

- ^ a b c Encke, J.F. (1854). "Beobachtung der Bellona, nebst Nachrichten über die Bilker Sternwarte" [Observation of Bellona and news of the Bilk Observatory]. Astronomische Nachrichten. 38 (9): 143–144. Bibcode:1854AN.....38..143.. doi:10.1002/asna.18540380907.

- ^ a b c Rümker, G. (1855). "Name und Zeichen des von Herrn R. Luther zu Bilk am 19. April entdeckten Planeten" [Name and symbol of the planet discovered by Mr. R. Luther at Bilk on the 19th of April]. Astronomische Nachrichten. 40 (24): 373–374. Bibcode:1855AN.....40Q.373L. doi:10.1002/asna.18550402405.

- ^ a b c Luther, R. (1856). "Schreiben des Herrn Dr. R. Luther, Directors der Sternwarte zu Bilk, an den Herausgeber" [A letter to the editor, from Dr. R. Luther, Director of the Bilk Observatory]. Astronomische Nachrichten. 42 (7): 107–108. Bibcode:1855AN.....42..107L. doi:10.1002/asna.18550420705.

- ^ a b Marth, A. (1854). "Elemente und Ephemeride des März 1 in London entdeckten Planeten Amphitrite" [Elements and ephemeris from the March 1st discovery of the planet Amphitrite, from London]. Astronomische Nachrichten. 38 (11): 167–168. Bibcode:1854AN.....38..167.. doi:10.1002/asna.18540381103.

- ^ a b c d e f JPL/NASA (April 22, 2015). "What is a Dwarf Planet?". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Faulks, David (May 28, 2016). "L2/16-080: Additional Symbols for Astrology" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Finlay, Alec (2008). One Hundred Year Star-Diary. Kielder Observatory Astronomical Society.

- ^ Unicode. "Proposed New Characters: The Pipeline". unicode.org. The Unicode Consortium. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ Chambers, George Frederick (1877). A Handbook of Descriptive Astronomy. Clarendon Press. pp. 920–921. ISBN 978-1-108-01475-5.

- ^ a b Olmsted, Dennis (1855). Letters on Astronomy. Harper. p. 288.

- ^ Österreichischer Universal-Kalender, 1849, p. xxxix

- ^ a b c Wilson, John (1899). A Treatise on English Punctuation. American Book Company. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-4255-3642-8.

- ^ Hencke, Karl Ludwig (1847). "Schreiben des Herrn Hencke an den Herausgeber" [A letter to the editor from Mr. Hencke]. Astronomische Nachrichten. 26 (610): 155–156. Bibcode:1847AN.....26..155H. doi:10.1002/asna.18480261007.

- ^ Oesterreichischer Universal-Kalender für das gemeine Jahr 1849 [Austrian Universal Calendar for the Common Year 1849]. Austria. 1849. p. xxxix.

- ^ a b c d e f Webster, Noah; Goodrich, Chauncey Allen (1864). Webster's Complete Dictionary of the English Language. p. 1,692.

- ^ Slipher, V.M. (1930). "The trans-Neptunian planet". Popular Astronomy. Vol. 38. p. 415. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ a b Faulks, David. "Astrological Plutos" (PDF). www.unicode.org. Unicode. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Deborah (May 4, 2022). "Out of this World: New Astronomy Symbols Approved for the Unicode Standard". unicode.org. The Unicode Consortium. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Miller, Kirk (October 26, 2021). "Unicode request for dwarf-planet symbols" (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ Pullen, Walter D. (September 18, 2021). "Dwarf Planets". astrolog.org. Archived from the original on October 19, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ Grundy, W.M.; Noll, K.S.; Buie, M.W.; Benecchi, S.D.; Ragozzine, D.; Roe, H.G. (December 2019). "The mutual orbit, mass, and density of transneptunian binary Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà ((229762) 2007 UK126)" (PDF). Icarus. 334: 30–38. Bibcode:2019Icar..334...30G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.12.037. S2CID 126574999. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2019.

- ^ Faulks, David (June 12, 2016). "Eris and Sedna Symbols" (PDF). unicode.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 8, 2017.

- ^ a b c Miller, Kirk (October 18, 2024). "Preliminary presentation of constellation symbols" (PDF). unicode.org. The Unicode Consortium. Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ The Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris for the Year 1833. The Board of Admiralty. 1831. p. 1.

- ^ The American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge, for the Year 1835. 1834. p. 47.

- ^

Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (6 ed.). 1823. p. 155.

... observe, that 60 seconds make a minute, 60 minutes make a degree, 30 degrees make a sign, and 12 signs make a circle.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Joyce, Jeremiah (1866). Scientific Dialogues for the Instruction and Entertainment of Young People. Bell and Daldy. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-145-49244-8.

- ^ The Nautical Almanac and the Astronomical Ephemeris for the year 1834. 1833. p. xiii. The 1834 edition of the Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris abandoned the use of numerical signs (among other innovations); compare the representation of (ecliptic) longitude in the editions for the years 1834 and 1833.

- ^ The IAU Style Manual (PDF). The International Astronomical Union (IAU). 1989. p. 34. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ Roy, Archie E.; David, Clarke (2003). Astronomy: Principles and practice. Taylor & Francis. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7503-0917-2.

- ^ King-Hele, Desmond (1992). A Tapestry of Orbits. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-39323-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Lewis; Short. A Latin Dictionary. Archived from the original on September 26, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2022 – via Tufts University Perseus Project.

- ^ Grego, Peter (2012). The Star Book: Stargazing throughout the seasons in the northern hemisphere. F+W Media.

- ^ Covington, Michael A. (2002). Celestial Objects for Modern Telescopes. Vol. 2. pp. 77–78.

- ^ Ridpath, John Clark, ed. (1897). The Standard American Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. p. 198.

- ^ a b c Tupman, G.L. (1877). "Observations of Comet I 1877". Astronomische Nachrichten. 89 (11): 169–170. Bibcode:1877AN.....89..169T. doi:10.1002/asna.18770891103. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ a b Miller, Kirk (December 23, 2021). "Unicode request for Lot of Fortune and eclipse symbols" (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ For example, Io entering Jupiter's shadow, the timing of which enabled Rømer to calculate the speed of light.

- ^ "Kirkhill Astronomical Pillar". May 23, 2018. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021.

![The symbol for the Sun in late Classical (4th c.) and medieval Byzantine (11th c.) manuscripts[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/80/Sun_symbol_%28late_classical_and_medieval_mss%29.png/120px-Sun_symbol_%28late_classical_and_medieval_mss%29.png)

![The symbol for the Moon in a medieval Byzantine manuscript (11th c.). The late Classical appearance was similar.[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/76/Moon_symbol_%28medieval_ms%29.png)

![The symbol for Mercury in late Classical (4th c.) and medieval Byzantine (11th c.) manuscripts[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/79/Mercury_symbol_%28late_classical_and_medieval_mss%29.png/120px-Mercury_symbol_%28late_classical_and_medieval_mss%29.png)

![The symbol for Venus in late Classical (4th c.) and medieval Byzantine (11th c.) manuscripts[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/25/Venus_symbol_%28late_classical_and_medieval_mss%29.png/120px-Venus_symbol_%28late_classical_and_medieval_mss%29.png)

![The symbol for Mars in late Classical (6th c.) and medieval Byzantine (11th c.) manuscripts[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Mars_symbol_%28late_classical_and_medieval_mss%29.png/120px-Mars_symbol_%28late_classical_and_medieval_mss%29.png)

![The symbol for Jupiter in late Classical (4th c.) and medieval Byzantine (11th c.) manuscripts[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Jupiter_symbol_%28late_classical_and_medieval_mss%29.png/120px-Jupiter_symbol_%28late_classical_and_medieval_mss%29.png)