Warren E. Burger

Warren E. Burger | |

|---|---|

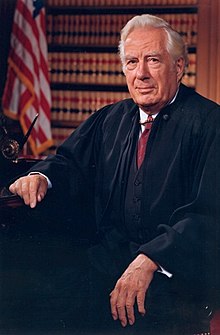

Official portrait, 1986 | |

| 15th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office June 23, 1969 – September 26, 1986 | |

| Nominated by | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Earl Warren |

| Succeeded by | William Rehnquist |

| 20th Chancellor of the College of William & Mary | |

| In office June 26, 1986 – July 1, 1993 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | Alvin Duke Chandler (1974) |

| Succeeded by | Margaret Thatcher |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit | |

| In office March 29, 1956 – June 23, 1969 | |

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Harold Montelle Stephens |

| Succeeded by | Malcolm Richard Wilkey |

| 11th United States Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Division | |

| In office May 1, 1953 – April 14, 1956 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Holmes Baldridge |

| Succeeded by | George Cochran Doub |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Warren Earl Burger September 17, 1907 Saint Paul, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | June 25, 1995 (aged 87) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Elvera Stromberg

(m. 1933; died 1994) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | St. Paul College of Law (LLB) |

| Signature |  |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Warren Earl Burger (September 17, 1907 – June 25, 1995) was an American attorney and jurist who served as the 15th chief justice of the United States from 1969 to 1986. Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Burger graduated from the St. Paul College of Law in 1931. He helped secure the Minnesota delegation's support for Dwight D. Eisenhower at the 1952 Republican National Convention. After Eisenhower won the 1952 presidential election, he appointed Burger to the position of Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Civil Division. In 1956, Eisenhower appointed Burger to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Burger served on this court until 1969 and became known as a critic of the Warren Court.

In 1969, President Richard Nixon nominated Burger to succeed Earl Warren as Chief Justice, and Burger won Senate confirmation with little opposition. He did not emerge as a strong intellectual force on the Court, but sought to improve the administration of the federal judiciary. He also helped establish the National Center for State Courts and the Supreme Court Historical Society. Burger remained on the Court until his retirement in 1986, when he became Chairman of the Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution. He was succeeded as Chief Justice by William H. Rehnquist, who had served as an associate justice since 1972.

In 1974, Burger wrote for a unanimous court in United States v. Nixon, which rejected Nixon's invocation of executive privilege in the wake of the Watergate scandal. The ruling played a major role in Nixon's resignation. Burger joined the majority in Roe v. Wade in holding that the right to privacy prohibited states from banning abortions. Later analyses have suggested that Burger joined the majority in Roe solely to prevent Justice William O. Douglas from controlling assignment of the opinion.[1] On the contrary, Burger would vote with the majority in Harris v. McRae in 1980, which formally launched the Hyde Amendment into effect. He later abandoned Roe v. Wade in Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. His majority opinion in INS v. Chadha struck down the one-house legislative veto.

Although Burger was nominated by a conservative president,[2] the Burger Court also delivered some of the most liberal decisions regarding abortion, capital punishment, religious establishment, sex discrimination, and school desegregation[3] during his tenure.[4]

Early life

[edit]Burger was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, in 1907, as one of seven children. His parents, Katharine (née Schnittger) and Charles Joseph Burger, a traveling salesman and railroad cargo inspector,[citation needed] were of Austrian German descent. He was raised Presbyterian.[5] His grandfather, Joseph Burger, was born in Bludenz, Vorarlberg, had emigrated from Tyrol, Austria and joined the Union Army when he was 13. Joseph Burger fought and was wounded in the Civil War, resulting in the loss of his right arm and was awarded the Medal of Honor at the age of 14. At age 16, Joseph Burger became one of the youngest captains in the Union Army.

Burger grew up on the family farm near the edge of Saint Paul. At age 8, he stayed home from school for a year after contracting polio.[6] Burger attended the same grade school as future Associate Justice Harry Blackmun.[7] He attended John A. Johnson High School, where he was president of the student council.[6] He competed in hockey, football, track, and swimming.[6] While in high school, he wrote articles on high school sports for local newspapers.[6] He graduated in 1925, and received a partial scholarship to attend Princeton University, which he declined because his family's finances were not sufficient to cover the remainder of his expenses.[6]

That same year, Burger also worked with the crew building the Robert Street Bridge, a crossing of the Mississippi River in Saint Paul that still exists. Concerned about the number of deaths on the project, he asked that a net be installed to catch anyone who fell, but was rebuffed by managers. In later years, Burger made a point of visiting the bridge whenever he came back to town.

Education and early career

[edit]Burger enrolled in extension classes at the University of Minnesota for two years while selling insurance for Mutual Life Insurance.[6] Afterward, he enrolled at St. Paul College of Law (which later became William Mitchell College of Law, now Mitchell Hamline School of Law), receiving his Bachelor of Laws, magna cum laude, in 1931.[6] He took a job at a St. Paul law firm.[6] In 1937, Burger served as the eighth president of the Saint Paul Jaycees.[6] He also taught for twenty-two years at William Mitchell.[6] A spinal condition prevented Burger from serving in the military during World War II; instead he supported the war effort at home, including service on Minnesota's emergency war labor board from 1942 to 1947.[6] From 1948 to 1953, he served on the governor of Minnesota's interracial commission, which worked on issues related to racial desegregation.[6] He also served as president of St. Paul's Council on Human Relations, which considered ways to improve the relationship between the city's police department and its minority residents.[6]

Burger's political career began uneventfully, but he soon rose to national prominence. He supported Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen's unsuccessful pursuit of the Republican nomination for president in 1948.[8] At the 1952 Republican National Convention, Burger played a key role in Dwight D. Eisenhower's nomination by leading the Minnesota delegates to change their votes from Stassen to Eisenhower after Stassen failed to obtain 10 percent of the vote, which freed the Minnesota delegation from their pledge to support him.

Assistant Attorney General

[edit]President Eisenhower appointed Burger as the Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Civil Division of the Justice Department.

In this role, he first argued in front of the Supreme Court. The case involved John P. Peters, a Yale University professor who worked as a consultant to the government. He had been discharged from his position on loyalty grounds. Supreme Court cases are usually argued by the Solicitor General, but he disagreed with the government's position and refused to argue the case. Burger lost the case. Shortly after, in Dalehite v. United States, 346 U.S. 15 (1953), Burger defended the United States against claims from the Texas City ship explosion disaster, successfully arguing that the Federal Tort Claims Act of 1947 did not allow a suit for negligence in policy making.

Court of Appeals service

[edit]Burger was nominated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 12, 1956, to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit vacated by Judge Harold M. Stephens. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on March 28, 1956, and received his commission on March 29, 1956. His service terminated on June 23, 1969, due to his elevation to the United States Supreme Court.

Chief Justice

[edit]Nomination and confirmation

[edit]

In June 1968, Chief Justice Earl Warren announced his retirement, effective on the confirmation of his successor. President Lyndon Johnson nominated sitting associate justice Abe Fortas to the position, but a Senate filibuster blocked his confirmation, and Johnson withdrew the nomination. Richard Nixon was elected president in November 1968 and Johnson did not make another nomination before his term as president ended on January 20, 1969.[9]

Burger was nominated by President Nixon to succeed Earl Warren on May 23, 1969.[10] The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary hearing on Burger's nomination took place on June 3, 1969.[11] It was characterized as having been friendly, and saw Burger as the sole individual to deliver testimony.[12] The hearing was reported as having taken only an hour and forty minutes.[13] Afterwards, the committee held a five-minute private session in which they voted unanimously to report favorably on his nomination.[11][12] The Senate confirmed Burger to the court by a 74–3 vote on June 9, 1969,[10][11] and he took the judicial oath of office on June 23, 1969.[14]

Remaking the Supreme Court had been a theme in Nixon's presidential campaign,[9] and he had pledged to appoint a strict constructionist as Chief Justice. Burger had first caught Nixon's eye through a letter of support he sent to Nixon during the 1952 Fund crisis,[15] and then again 15 years later when the magazine U.S. News & World Report reprinted a 1967 speech that Burger had given at Ripon College.[16] In it, Burger compared the United States judicial system to those of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark:

I assume that no one will take issue with me when I say that these North European countries are as enlightened as the United States in the value they place on the individual and on human dignity. [Those countries] do not consider it necessary to use a device like our Fifth Amendment, under which an accused person may not be required to testify. They go swiftly, efficiently and directly to the question of whether the accused is guilty. No nation on earth goes to such lengths or takes such pains to provide safeguards as we do, once an accused person is called before the bar of justice and until his case is completed.

Through speeches like this, Burger became known as a critic of Chief Justice Warren and an advocate of a literal, strict-constructionist reading of the U.S. Constitution. Nixon's agreement with these views, being expressed by a readily confirmable, sitting federal appellate judge, led to the nomination.

According to President Nixon's memoirs, he had asked Burger in the spring of 1970 to be prepared to run for president in 1972 if the political repercussions of the Cambodia invasion were too negative for him to endure. A few years later, Burger was on Nixon's short list of vice presidential candidates following the resignation of Spiro Agnew in October 1973, before Gerald Ford was appointed to succeed him.

Jurisprudence

[edit]

The Court issued a unanimous ruling, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971), supporting busing to reduce de facto racial segregation in schools. However, Burger wrote the majority opinion for Milliken v. Bradley (1974), which upheld de facto school segregation across school district lines if segregationist policy was not explicitly stated by all of the districts involved. In United States v. U.S. District Court (1972), the Burger Court issued another unanimous ruling against the Nixon administration's desire to invalidate the need for a search warrant and the requirements of the Fourth Amendment in cases of domestic surveillance. Then, only two weeks later in Furman v. Georgia (1972), the Court, in a 5–4 decision, invalidated all death penalty laws then in force although Burger dissented from that decision. In the most controversial ruling of his term, Roe v. Wade (1973), Burger voted with the majority to recognize a broad right to privacy that prohibited states from banning abortions. However, Burger later abandoned Roe in Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (1986).

On July 24, 1974, Burger led the Court in a unanimous decision in United States v. Nixon, arising from Nixon's attempt to keep several memos and tapes relating to the Watergate scandal private. As documented in Woodward and Armstrong's The Brethren and elsewhere, Burger's original feelings on the case were that Watergate was merely a political battle, and Burger "didn't see what they did wrong".[17] The actual final opinion was largely Brennan's work, but each justice wrote at least a rough draft of a particular section.[18] Burger was originally to vote in favor of Nixon but tactically changed his vote to assign the opinion to himself and to restrain the opinion's rhetoric.[19] Burger's first draft of the opinion wrote that executive privilege could be invoked when it dealt with a "core function" of the presidency and that in some cases, the executive could be supreme.[20] However, the other justices were able to convince Burger to excise that language from the opinion: the judicial branch alone would have the power to determine whether something can be shielded under an assertion of executive privilege.[21]

Burger joined the majority decision in Board of Education of the Hendrick Hudson Central School District v. Rowley, which was the first special education law case decided by the Supreme Court. The Court upheld the constitutionality of Individual Education Plans, but also held that the school district did not have to provide every service necessary in order to maximize a child's potential.

Burger also emphasized the maintenance of checks and balances among the branches of government. In Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Chadha (1983), he held for the majority that Congress could not reserve a legislative veto over executive branch actions.

On issues involving criminal law and procedure, Burger remained reliably conservative. He dissented in Solem v. Helm, which held that a life sentence for a phony check was unconstitutional. He once stated personal opposition to the death penalty in his Furman v. Georgia dissent,[22] but defended it as constitutional.

Leadership

[edit]

Rather than dominating the Court, Burger sought to improve administration both within the Court and within the nation's legal system. Criticizing some advocates as unprepared, Burger created training venues for state and local government advocates.[23] He also helped found the National Center for State Courts, which is now in Williamsburg, Virginia, as well as the Institute for Court Management, and National Institute of Corrections to provide professional training for judges, clerks, and prison guards.[24] Burger also began a tradition of annually delivering a State of the Judiciary speech to the American Bar Association, many of whose members had been alienated by the Warren Court. However, some detractors thought his emphasis on the mechanics of the judicial system trivialized the office of chief justice.[citation needed] Despite his reputation for being imperious, he was well-liked by the law clerks and judicial fellows who worked with him.[25]

Burger drew internal controversy within the Supreme Court throughout his tenure, as was revealed in Woodward and Armstrong's The Brethren. Although Sen. Everett Dirksen noted Burger "looked, sounded, and acted like a chief justice," the reporters depicted Burger as an ineffective chief justice who was not seriously respected by his colleagues for his alleged pomposity and lack of legal acumen.[citation needed] Woodward and Armstrong's sources indicated that some of the other justices were annoyed by Burger's practice of switching his vote in conference or simply not announcing his vote so that he could control opinion assignments. "Burger repeatedly irked his colleagues by changing his vote to remain in the majority, and by rewarding his friends with choice assignments and punishing his foes with dreary ones."[26] Burger would also try to influence the course of events in a case by circulating a pre-emptive opinion.[27] Clerks mocked him for his perceived egotism and intense homophobia, and Justice Lewis Powell allegedly referred to him as "the great white doughnut", an attack on both his intellect and physical appearance.[28]

Consequently, the Burger Court was described as his "in name only".[29] Time magazine called him "plodding" and "standoffish"[29] as well as "pompous", "aloof", and unpopular.[26] Burger was a constant irritant on the Court's group dynamic, according to The New York Times' Linda Greenhouse.[30] Jeffrey Toobin wrote in his book The Nine that by the time of his departure in 1986, Burger had alienated all of his colleagues to one degree or another.[31] In particular, Associate Justice Potter Stewart, who had been considered a candidate to succeed Warren as chief justice, was so discontented with Burger that he became the primary source for Woodward and Armstrong when they wrote The Brethren.

Greenhouse pointed to INS v. Chadha as evidence of Burger's "foundering leadership". Burger would cause the case to be delayed for over twenty months although there had been five votes to affirm the appeals court's finding of unconstitutionality after the case had been first argued: Brennan, Marshall, Blackmun, Powell, and Stevens. Burger did not allow an opinion to be assigned, first by asking for a special conference on the case and then by delaying the case for reargument when that conference fell through even though he never held a formal vote on holding the case over for reargument.[32]

Views on women judges

[edit]No women served on the Supreme Court until 1981, and Burger was strongly opposed to giving a seat to a female judge. In 1971, President Nixon considered nominating California state Appellate Judge Mildred Lillie to the Supreme Court. Former White House Counsel John Dean had said that the greatest opposition to Lillie came from Chief Justice Burger.[33] Dean indicated that Burger threatened to resign over the nomination.[34]

Views on homosexuality

[edit]Burger was deeply prejudiced against gay people to an extent which bordered on hysteria.[35] Burger sent Byron White, who wrote the majority opinion in Bowers v. Hardwick upholding laws banning homosexual relations between consenting adults, a letter telling him to condemn homosexuality in his opinion. White refused.[36] When Lewis Powell voted to strike down the anti-gay laws, Burger aggressively lobbied him to change his mind, and sent him a letter so hostile towards homosexuals that Powell mockingly described it as "nonsense".[37] Burger wrote his own opinion attacking homosexuality, quoting a description of it as "an infamous crime against nature, of deeper malignity than rape, and an act not fit to be named, the very mention of which is an affront to human nature", and noted, with apparent approval, that homosexuals were once executed.[38][39] Burger's language mobilized gay rights advocates to work to overturn sodomy laws, eventually succeeding in the 2003 case Lawrence v. Texas.[40]

Later life and death

[edit]

Burger left office on September 26, 1986,[14] in part to lead the campaign to mark the bicentennial of the United States Constitution. He was succeeded as chief justice by William Rehnquist.[41] He served longer than any other chief justice appointed in the 20th century.[42]

In 1987, Princeton University's American Whig-Cliosophic Society awarded Burger the James Madison Award for Distinguished Public Service.[43] In 1988, he was awarded the prestigious United States Military Academy's Sylvanus Thayer Award as well as the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In a 1991 appearance on the MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, Burger stated that the notion that the Second Amendment guaranteed an unlimited individual right to obtain any kind of weapon "has been the subject of one of the greatest pieces of fraud, I repeat the word 'fraud,' on the American public by special interest groups".[44]

On June 25, 1995, Burger died from congestive heart failure at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington, at the age of 87.[45] All of his papers were donated to the College of William and Mary, where he had served as Chancellor; however, they will not be open to the public until ten years after the death of Sandra Day O'Connor in 2033-2034, the last surviving member of the Burger Court, per the donor agreement. O'Connor died on December 1, 2023.[46][47]

Burger's casket lay in repose in the Great Hall of the United States Supreme Court Building. His remains are interred at Arlington National Cemetery.[48]

Legacy

[edit]As chief justice, Burger was instrumental in founding the Supreme Court Historical Society and was its first president. Burger is often cited as one of the foundational proponents of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), particularly in its ability to ameliorate an overloaded justice system. In a speech given in front of the American Bar Association, Chief Justice Burger lamented the state of the justice system in 1984, saying, "Our system is too costly, too painful, too destructive, too inefficient for a truly civilized people. To rely on the adversary process as the principal means of resolving conflicting claims is a mistake that must be corrected."[49] The Warren E. Burger Federal Courthouse[50] in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and the Warren E. Burger Library[51] at his alma mater, the Mitchell Hamline School of Law (formerly the William Mitchell College of Law, and the St. Paul College of Law at the time of Burger's attendance) are named in his honor.

Family and personal life

[edit]He married Elvera Stromberg in 1933. They had two children, Wade Allen Burger (1936–2002) and Margaret Elizabeth Burger (1946–2017).[52] Elvera Burger died at their home in Washington, D.C., on May 30, 1994, at the age of 86.[48]

See also

[edit]- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States by court composition

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Chief Justice)

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Burger Court

References

[edit]- ^ Woodward, Bob; Armstrong, Scott (May 31, 2011). The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1439126349. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ "Perceived Qualifications and Ideology of Supreme Court Nominees, 1937–2012" (PDF). SUNY at Stony Brook. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ Barker, Lucius J. (Autumn 1973). "Black Americans and the Burger Court: Implications for the Political System". Washington University Law Review. 1973 (4): 747–777. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2017 – via Washington University Law Review Archive.

- ^ Earl M. Maltz, The Coming of the Nixon Court: The 1972 Term and the Transformation of Constitutional Law (University Press of Kansas; 2016)

- ^ Vinson, Henry (December 4, 2017). A Model Conservative. Christian Faith Publishing. ISBN 9781641142687.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Warren E. Burger (1907–1995)". Uscivilliberties.org. Civil Liberties in the United States. December 1, 2012. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- ^ https://www.twincities.com/2004/03/05/as-friends-and-rivals-blackmun-and-burger-swayed-the-court/

- ^ Osro Cobb, Osro Cobb of Arkansas: Memoirs of Historical Significance, Carol Griffee, ed. (Little Rock, Arkansas: Rose Publishing Company, 1989), p. 99

- ^ a b Hindley, Meredith (October 2009). "Supremely Contentious: The Transformation of "Advice and Consent"". Humanities. Vol. 30, no. 5. National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ a b "Supreme Court Nominations (1789-Present)". Washington, D.C.: United States Senate. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c McMillion, Barry J.; Rutkus, Denis Steven (July 6, 2018). "Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2017: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Graham, Fred P. (June 4, 1969). "Burger Approved by Senate Panel; A Unanimous Vote Follows Friendly Questioning -- Protester Is Barred". The New York Times. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ Biskupic, Joan (June 26, 1995). "Ex-chief Justice Warren Burger Dead at Age 87". Washington Post. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Justices 1789 to Present". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "The Checkers Speech After 60 Years". The Atlantic. September 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ Morris, Jeffrey B. (June 18, 2019). "The Fiftieth Anniversary of Warren Burger's Appointment as Chief Justice". Yorba Linda, California: Richard Nixon foundation. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Eisler 1993, p. 251.

- ^ Eisler 1993, pp. 251–253.

- ^ Eisler 1993, p. 252.

- ^ Eisler 1993, p. 254.

- ^ Eisler 1993, pp. 254–255

- ^ "Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972)". Justia Law. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Warren E. Burger, Conference on Supreme Court Advocacy, 33 Catholic U. L.Rev. 525–526 (1984)

- ^ Christensen, George A., Journal of Supreme Court History Volume 33 Issue 1, Pages 17–41 (February 19, 2008), Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited, University of Alabama.

- ^ Bonventre, Vincent (1995), Professional Responsibility: Conclusion, 46 Syracuse L. Rev. 765, 793 (1995), Syracuse_Law_Review.

- ^ a b "Reagan's Mr. Right". Time. June 30, 1986. Archived from the original on December 20, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, p. 157.

- ^ Murdoch, Joyce; Price, Deborah (May 9, 2002). Courting Justice. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465015146. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "Reagan's Mr. Right". Time. June 30, 1986. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, p. 234.

- ^ Toobin, Jeffrey (2005), The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, Doubleday.

- ^ Greenhouse 2005, pp. 154–157.

- ^ Hannah Brenner Johnson; Renee Knake Jefferson (May 12, 2020). Shortlisted: Women in the Shadows of the Supreme Court. NYU Press. ISBN 9781479816019.

- ^ "'The Rehnquist Choice' by John Dean". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. December 30, 2001. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- ^ Collins (August 15, 2017). Accidental Activists. University of North Texas press. p. 66. ISBN 9781574417036.

- ^ "Justice White's papers reveal Bowers debate". Law.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Urofsky (April 27, 2018). Supreme Decisions. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780429972621.

- ^ Burger, Warren E. "Bowers v. Hardwick/ Concurrence Burger". Justia. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Price, Deborah; Murdoch, Joyce (May 9, 2002). Courting Justice. Basic Books. p. 319. ISBN 9780465015146. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ Sheyn, Elizabeth. "The short heard around the LGBT world" (PDF). Journal of Race, Gender and Ethnicity. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Examining the legacy of Chief Justice Warren Burger". constitution Daily. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: National Constitution Center. June 9, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Supreme Court History, the Burger Court Archived October 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at Supreme Court Historical Society.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 26, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Stevens, John Paul (April 11, 2014). "Opinion: The five extra words that can fix the Second Amendment". Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ Linda Greenhouse (June 26, 1995). "Warren E. Burger Is Dead at 87; Was Chief Justice for 17 Years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Warren E. Burger Collection". William & Mary Libraries. December 8, 2010. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Schechter, Ute (December 8, 2010). "Warren E. Burger Collection". William & Mary Libraries. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

In accordance with the donor agreement, the Warren E. Burger Papers are closed to researchers until at least 2032.* * The deed of gift specifies that the papers are to remain closed to researchers until 10 years after the last Justice who served with Warren E. Burger on the Supreme Court has passed away, or 2026, whichever comes later.

- ^ a b "Elvera S. Burger, Supreme Court Spouse". www.arlingtoncemetery.net. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "FSM 3 Intrm. 015-017". www.fsmlaw.org. Archived from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ^ "Warren E. Burger Federal Building — U.S. Courthouse - St. Paul, Minnesota". www.ryancompanies.com. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ^ "Warren E. Burger Library – Mitchell Hamline School of Law". MitchellHamline.edu. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ "Mary Rose Obituary". Washington Post. Legacy.com. December 24, 2017. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Barker, Lucius J. Black Americans and the Burger Court: Implications for the Political System, 1973 Wash. U. L. Q. 747 (1973).

- Eisler, Kim Isaac (1993), A Justice for All: William J. Brennan, Jr., and the Decisions That Transformed America, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-76787-9

- Greenhouse, Linda. Nixon Appointee Eased Supreme Court Away from Liberal Era, The New York Times, June 26, 1995.

- Greenhouse, Linda (2005), Becoming Justice Blackmun, Times Books, ISBN 0805080570

- Schwartz, Bernard. A History of the Supreme Court Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0-19-509387-2.

- Schwartz, Bernard, ed. The Burger Court: Counter-Revolution or Confirmation? Oxford University Press, 1998 ISBN 0-19-512259-3.

- Woodward, Robert; Armstrong, Scott (1979). The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court. New York. ISBN 978-0-380-52183-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

[edit]- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Blasi, Vincent (1983). The Burger Court : the counter-revolution that wasn't (3rd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300029413.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Graetz, Michael J., and Linda Greenhouse, eds. The Burger Court and the Rise of the Judicial Right (Simon & Schuster, 2016). xii, 468 pp.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

External links

[edit]- Warren Earl Burger at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Ariens, Michael, Warren E. Burger.

- Oyez, Supreme Court Media, Warren E. Burger.

- Warren E. Burger at Archived October 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Supreme Court Historical Society

- Supreme Court History, the Burger Court Archived October 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at Supreme Court Historical Society.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1907 births

- 1995 deaths

- 20th-century American judges

- American Presbyterians

- American lawyers with disabilities

- American legal scholars

- American people of Austrian descent

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Chancellors of the College of William & Mary

- Chief justices of the United States

- Deaths from congestive heart failure

- Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit

- Lawyers from Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Minnesota Republicans

- Polio survivors

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- United States assistant attorneys general for the Civil Division

- United States court of appeals judges appointed by Dwight D. Eisenhower

- United States federal judges appointed by Richard Nixon

- University of Minnesota alumni

- Washington, D.C., Republicans

- Watergate scandal investigators

- William Mitchell College of Law alumni