Transportation in Boston

Transportation in Boston includes roadway, subway, regional rail, air, and sea options for passenger and freight transit in Boston, Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) operates the Port of Boston, which includes a container shipping facility in South Boston, and Logan International Airport, in East Boston. The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) operates bus, subway, short-distance rail, and water ferry passenger services throughout the city and region. Amtrak operates passenger rail service to and from major Northeastern cities, and a major bus terminal at South Station is served by varied intercity bus companies. The city is bisected by major highways I-90 and I-93, the intersection of which has undergone a major renovation, nicknamed the Big Dig.

Road transportation

[edit]Road infrastructure

[edit]

Except for the Back Bay and part of the South Boston neighborhoods, Boston has no street grid. The City of Boston, composed of many smaller towns annexed over the years, retained most of the pre-existing street names, resulting in many duplicates throughout the city.[citation needed]

Expressways and freeways in and around Greater Boston are laid out with two circumferential expressways: Interstate 495 and Route 128. The circumferential routes are intersected by several radial highways, including:

- Interstate 93 (the Northern/Southeast Expressway), which extends north of the city into New Hampshire, and southward to the Braintree Split,

- Interstate 90 (the Massachusetts Turnpike), connecting Boston with Worcester and Springfield,

- United States Route 1 (the Northeast Expressway/Newburyport Turnpike), crossing the Tobin Bridge and eventually serving Newburyport,

- Storrow Drive, an unnumbered high-speed parkway along the Charles River connecting downtown Boston with the Route 2 corridor,

- U.S. Route 20, a route running from Kenmore Square to Newport, Oregon — although it is not an expressway.

- Massachusetts Route 2 (the Concord Turnpike/Alewife Brook Parkway), serving the northwestern suburbs including Lexington, Concord and Fitchburg,

- Massachusetts Route 3 (the Pilgrims Highway), connecting Boston with Cape Cod,

- United States Route 3 (the Northwest Expressway), a functionally separate highway serving Lowell, Burlington and other suburbs in between Route 2 and I-93,

- Massachusetts Route 24, serving the interior southern suburbs, including Brockton, Taunton and Fall River

- and Interstate 95, indirectly connecting Boston with Rhode Island via I-93.

By the early 1990s, traffic on the elevated downtown portions of I-93 and Route 1 (the Central Artery) was 190,000 vehicles per day, with an accident rate four times the national average for urban interstates. Traffic was bumper-to-bumper for six to eight hours per day, with projections of traffic jams doubling by 2010. Also, the elevated structure itself was decaying, after more than a half century of continuous use. For most of the 1990s and early 2000s, driving in Boston was disrupted by the Big Dig, the most expensive (roughly $14 billion) road project in the history of the US.

After more than 15 years of disruption, The Big Dig, along with other highway projects, provided less than 10 years of relief before congestion returned to the levels seen in "prerecession 2005, when the Big Dig was almost complete and marketed as the solution to gridlock for commuters ... analyses would conclude that the added capacity attracted more drivers, and pushed the traffic bottlenecks farther into the suburbs."[1] However even without the big dig the raised road was structurally deficient and needed rebuilding or replacement.

Boston remains one of the most congested metropolitan areas in the US. The complex and still-changing road network, with many one-way streets and time-based traffic restrictions, has led many Boston travelers to consider an up-to-date GPS navigation map system a necessity.

Walking and bicycling

[edit]

Boston is known to travel agents as "America's Walking City", has been rated as the third most walkable city in the US by Walk Score, and also has a high Transit Score.[2]

Boston is a compact city, sized right for walking or bicycling. According to a Prevention magazine report in 2003, the city has the highest percentage of on-foot commuters of any city in the United States. In 2000, 13.36% of Boston commuters walked to work according to the US Census. This was the highest of any major US city, bested only by college towns such as nearby Cambridge. Most of the area's cities and towns have standing committees devoted to improvements to the bicycle and pedestrian environment. The first pedestrian advocacy organization in the United States, WalkBoston, was started in Boston in 1990, and helped start the national pedestrian advocacy organization America Walks.

Cycling is popular in Boston, for both recreation and commuting. Some bicycle paths are marked on some roadways, but very few completely separated paths are available to cyclists. The Minuteman Bikeway (which runs through several suburbs northwest of Boston) and the Charles River bike paths are popular with recreational cyclists and tourists. The Emerald Necklace system of parklands and parkways, pioneered by Frederick Law Olmsted and his sons, provides some more pleasant alternative routes for cyclists. The Southwest Corridor also provides cycling infrastructure,[3] as does the East Boston Greenway.[4] Many MBTA riders use a bicycle to get to a nearby station, and the number of bicycle racks and lockers has been increased.[5]

However Bicycling magazine, in its March 2006 issue, named the city as one of its three worst cities in the United States for cycling.[6] The distinction was earned for "lousy roads, scarce and unconnected bike lanes and bike-friendly gestures from City Hall that go nowhere—such as hiring a bike coordinator in 2001, only to cut the position two years later".[7] Neighboring Cambridge earned an honorable mention as one of the best cities for cycling with a population of 75,000-200,000.[8]

Since September 2007, when Mayor Thomas Menino started a bicycle program called Boston Bikes with a goal of improving bicycling conditions by adding bike lanes and racks and offering bikeshare programs, the city has improved accommodations for bicyclists in a number of ways.[9][10] The least visible improvement is zoning and building code changes to encourage showering and locker facilities in major office buildings. Better signage and lane markings for bicyclists are starting to appear. More visible enforcement of traffic regulations on motorists, bicyclists, and pedestrians has commenced.[11][12][13][14]

Boston has an active Critical Mass ride group, and MassBike is a bike advocacy group active in supporting cyclists in the area.[15][16] The LivableStreets Alliance, headquartered in Cambridge, is an advocacy group for bicyclists, pedestrians, and walkable neighborhoods.[17]

Maps and guides

[edit]

The Boston regional Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) publishes a large and detailed "Greater Boston Cycling & Walking Map", which it distributes free of charge.[18] The map is also available online and in downloadable form, and revisions are solicited from the general public.

In addition, a small private company called Rubel BikeMaps has for many years published and distributed an extensive lineup of books and maps covering Boston, the state of Massachusetts, and nearby areas of New England.[19] These publications are for sale at many bicycle shops, and online. Because of recent expansion of bike lanes and other facilities, plus increased input from the public, it is important to use the most recent editions of these maps and guides.

Rubel BikeMaps also publishes Car-Free in Boston:a Guide for Locals and Visitors, still in its 10th edition as of 2015[update].[20] Prepared by the Association for Public Transportation (APT), this book contains extensive information useful to bicyclists and pedestrians alike, including coverage of intermodal travel and handicapped accessibility. Although the general overview and travel tips are largely still relevant, this classic book has not been updated since 2003, and must be supplemented by current online information.

With widespread use of smartphones and tablet computers, online mapping services such as Google Maps have become popular aids for pedestrians, cyclists, and motorists. The MBTA was one of the earliest large transit agencies to embrace the Open Data philosophy, making route, scheduling, and real-time vehicle location information publicly available in the standard GTFS format.[21] As a result, many third-party apps are available on a number of hardware platforms, allowing riders a wide range of choices in obtaining travel information.[22] Google Maps has started to present maps of the interiors of underground subway stations, and this information is available on Android and iOS smartphones, as well as web browsers.

Buses

[edit]

162 MBTA bus routes operate within the Greater Boston area, with a combined ridership of approximately 375,000 one-way trips per day, making it the seventh-busiest local bus agency in the country. Included within the MBTA system are four of the few remaining trackless trolley lines in the US (71, 72, 73 and 77A), although these principally operate in the adjoining city of Cambridge. The bus fare is $1.70 with a CharlieCard, or $2 with a CharlieTicket or cash; monthly commuter passes are available, as are reduced fare transfers between most bus lines and the subway.

In an effort to provide service intermediate in speed and capacity between subways and buses, the MBTA has begun projects using bus rapid transit (BRT) technology. The MBTA has one BRT line, the Silver Line, although this operates in two discontinuous sections. The Silver Line operates in part via dedicated trolleybus tunnel, in part via on-street reserved bus lanes, and in part mixed with general street traffic. Service through the trolleybus tunnel is by dual-mode buses, which operate electrically in the tunnel and within a short section on the surface, and which use diesel power for the rest of the route.

Massport operates the Logan Express, an express bus service between Logan International Airport and suburban park-and-ride lots.

Several privately owned commuter bus services take passengers between the city and suburbs.[23] Transportation Management Associations[24] also run public shuttles to specific employment centers, such as the EZ Ride for Kendall Square;[25] and the Route 128 Business Council shuttles around Alewife, Needham, and Waltham;[26] Partners HealthCare runs public shuttles among its locations.[27] The MASCO TMA operates six commuter shuttles for the use of Longwood Medical Area employees and students[28] run by the MASCO TMA for the Longwood Medical Area. The MASCO M2 shuttle between Harvard Square and the LMA via Massachusetts Avenue is available for public use, though tickets or cash card must be purchased in advance.[29] Many colleges and universities also run private shuttles for students and employees.

In June 2014, the Cambridge-based startup Bridj began running "data driven" bus service in core neighborhoods.[30] It uses a mixture of fixed and dynamic routes and pricing, depending on where and when registered members say they want to go.[31]

Parking

[edit]Since automobiles did not exist in 1630, when Boston was first settled, parking was not a consideration. The city that sprung up around and away from the original North End neighborhood accommodates cars only awkwardly; parking comes at a premium throughout the city. Off-street parking spaces have sold for more than $160,000 on Beacon Hill.[32] On-street parking is the norm in many sections, and the city created a resident permit parking program to reserve street space for permanent residents in certain neighborhoods. The parking permits are free to Boston residents, however, and the program is overused; permitted spaces remain scarce.[33] Meters citywide are priced at $1.25 per hour, and metered spaces are also often difficult to find.

The number of public parking spaces downtown has been capped since the mid-1970s.[34] The number of parking spaces in East and South Boston, and the hours that they may be used, also is restricted by state regulation. This is part of the state Department of Environmental Protection's plan, approved by the United States Environmental Protection Agency to address the non-compliance of the region with the mandatory National Ambient Air Quality Standards for ozone.[35]

The MBTA operates several large park and ride facilities on its subway and commuter rail lines, close to major highways, providing access to downtown. While most of these tend to fill up with commuters on weekday mornings, they provide a good place for visitors to leave their cars and see the city without parking hassles on evenings and weekends.

Rail transportation

[edit]Boston has two discrete rail networks. One of these, the MBTA, widely nicknamed "the T", includes elements of light rail/streetcar operation as well as traditional subway technology. (The Red, Orange, Blue, and Green Lines have no physical rail interconnections with each other, though they are all operated by the MBTA and exchange passengers in shared stations.) The second network forms the Boston area portion of the North American rail network, and provides commuter rail, intercity passenger rail and freight rail services.

Although the two networks are essentially unconnected, they do in some places run alongside each other in the same right of way. Interchange stations allow interchange of passengers, but not trains, between subway and commuter rail services. Parts of the subway network also use former common user rail rights of way.

Subway network

[edit]

Boston has the oldest subway system in North America, with the first underground streetcar traffic dating back to 1897. Today the whole subway network is owned and operated by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA).

In the early 1960s, the then-newly-formed MBTA hired Cambridge Seven Associates to help develop a new brand identity. Cambridge Seven came up with a circled T to represent such concepts as "transit", "transportation" and "tunnel." Today, Bostonians call their rapid transit network "the T", and it is the fourth busiest in the country, with daily ridership of 273,000 trips on its heavy rail and 90,700 on its light rail.[36] This compares with the Washington Metro's heavy rail daily ridership of 326,300, the Chicago 'L''s 334,200, and Los Angeles's 76,800, but is overshadowed by New York City's 6.335 million average daily weekday trips.[36]

The one-way fare is $2.40. Monthly commuter passes, and day and week visitor's passes are also available for purchase.[37] There are four subway lines in the metropolitan Boston area: the Red Line, Green Line, Orange Line, and Blue Line. The colors of each line have a symbolic meaning: the Blue Line runs under Boston Harbor; the Red Line used to terminate at Harvard University (whose school color is crimson); the Orange Line used to run along Washington Street, which was once called Orange Street; and the Green Line runs along parts of the Emerald Necklace into the leafy suburbs of Brookline and Newton.[38]

The Green Line is actually four different lines; it starts as one trunk line but then splits into four different branches, the B (Boston College), C (Cleveland Circle), D (Riverside) and E (Heath Street) trains. Because the split is only relevant on the outbound direction of travel, one may take any train inbound, but when going outbound one must be careful to board the correct train. The Red Line splits as well, with southbound trains going either to Braintree or Ashmont.

Though most of Boston's rapid transit network is powered via third rail, the outermost portions of the Blue Line, as well as all of the Green Line and Mattapan Line, are powered via overhead lines. The name "subway" is something of a misnomer; as with other systems, large segments run above ground when far from the city's downtown. Additionally, the Green and Mattapan Lines are technically light-rail services, using LRVs and streetcars rather than typical multiple unit heavy railcar equipment. The Ashmont–Mattapan line uses refurbished classic pre-war "PCC" trolleys on an exclusive right of way; the Green Line relies on modern high-capacity LRV cars from Japan and Italy.

Like the New York City Subway, Boston's subway system in theory does keep to an exact fixed schedule. Starting around 2011, the MBTA introduced overhead displays at the train platform level which indicate estimated arrival times for the next two trains in each direction. In addition, real-time information about train location (and bus location) is available via an Open Data protocol on the Internet, enabling a large number of third-party smartphone apps and web sites to display expected arrival times throughout the MBTA system. The Green Line relies more on operators than its signal system compared to other lines, especially where trams are driven across or even in automobile lanes on surface rails. Due to a sparsity of data collected by the existing system, real-time Green Line arrival predictions are not expected until tracking infrastructure upgrades are completed in 2015.[39][needs update]

Elevated sections

[edit]Despite the first rapid transit segment being built underground, many later parts were built as elevated railways.[dubious – discuss] A century later, most of these elevated railway sections have been replaced by cut or tunnel routing. The only remaining classic elevated structures are the Green Line's Lechmere Viaduct, including the Science Park and Lechmere stations, and a short segment of the Red Line at Charles-MGH, connecting the tunnel under Beacon Hill to the Longfellow Bridge.

The Boston Elevated Railway was the company that owned all the elevateds and subways. The following Els once existed:

- Causeway Street Elevated (closed 2004), from the Haymarket Incline to the Lechmere Viaduct

- Washington Street Elevated (closed 1987), from Forest Hills to an incline north of the Masspike

- Charlestown Elevated (closed April 4, 1975), from the Haymarket Incline to Everett

- Atlantic Avenue Elevated (closed 1938), from the Washington Street El at the Castle Street Wye at Herald Street (Tower 'D') to the Charlestown El and Causeway Street El at North Station (Tower 'C')

Common user rail network

[edit]Unlike the subway, which is owned and operated by the MBTA, the common user network is owned and operated by a mixture of various public and private sector bodies. In the Boston area, trackage is owned by a mixture of the MBTA and several freight railroads. Commuter rail services are operated by the Keolis Commuter Services (KCS)[40] under contract to the MBTA, intercity passenger services are operated by Amtrak, and freight services are operated by the various freight railroads. Trackage rights allow trains of one operator to make use of tracks owned by another.[41]

Commuter rail

[edit]

The MBTA commuter rail system brings people from as far away as Worcester and Providence (Rhode Island) into Boston. There are approximately 125,000 one-way trips on the commuter rail each day, making it the fifth-busiest commuter rail system in the country, outranked only by the various systems serving New York and Chicago suburbs.

There are two major rail terminals in Boston: North Station and South Station. Commuter rail lines from the North Shore and northwestern suburbs begin and terminate at North Station; lines from the South Shore and the west start and end at South Station. There is no direct rail connection between North Station and South Station, so that interchange between the two stations generally requires the use of two different subway lines (Red/Orange or Red/Green). However, passengers on commuter lines serving Back Bay Station can interchange directly from there to North Station using the Orange Line, and passengers on the Fitchburg Line can interchange directly from Porter to South Station using the Red Line.

Intercity rail

[edit]

Boston is served by four intercity rail services, all operated by Amtrak. The Acela and Northeast Regional services both operate on the Northeast Corridor to and from Washington, D.C., with stops in places such as New York City and Philadelphia. A branch of the Lake Shore Limited service operates to and from Chicago. The Downeaster service operates to and from Brunswick, Maine.[42]

The Northeast Corridor services terminate at South Station, as does the Lake Shore Limited. The Downeaster service terminates at North Station, primarily because the Downeaster Amtrak line is intended for points north of downtown. The Northeast Corridor and Lake Shore Limited services also stop at Back Bay station. The lack of a direct rail connection between North Station and South Station means that passengers transferring to and from the Downeaster are faced with a transfer between stations. Although most such transfers can be achieved using the Orange Line between Back Bay and North Station, Amtrak recommends passengers with luggage to use a taxi.[42][43]

Within the Boston area, most Amtrak services operate over commuter rail track owned by the MBTA, who also own the Northeast Corridor track as far as the Rhode Island state line.[41]

Freight rail

[edit]CSX is the only class I railroad serving the Boston area, which it reaches by its Boston Subdivision line to Springfield, and by trackage rights over the Northeast Corridor. CSX also has trackage rights over much of the southern half of the MBTA's commuter rail network. In February 2013, CSX moved freight operations from its Beacon Park Yard in Allston[41] to a newly refurbished double stack intermodal yard in Worcester and a new transload facility in Westborough.[44]

The other significant freight railroad in the Boston area is Pan Am Railways (PAR; formerly known as the Guilford Rail System). PAR is a class II railroad that operates lines to the north and west of Boston, reaching destinations in New Hampshire, Maine and New York as well as Massachusetts. It also has trackage rights over much of the northern half of the MBTA's commuter rail network. In May 2008, PAR announced a venture with Norfolk Southern Railway to create a jointly owned freight corridor, branded the Patriot Corridor, linking Boston to a newly refurbished intermodal yard in Mechanicville, New York, just north of Albany.[41][45]

Only a few rail freight customers remain in or near Boston, including a chemical packager in Allston, and food distribution facilities and a scrap metal processor in Everett. The Class III Fore River Railroad serves two major customers in Quincy. A plan to ship ethanol by rail to a gasoline mixing plant in Revere was reviewed in 2013.[46][47][48] In the face of community opposition and pressure from the state legislature, the company withdrew its proposal on July 2, days before the Lac-Mégantic derailment.[49]

Water transportation

[edit]Port of Boston

[edit]

The Port of Boston is a major seaport and the largest port in Massachusetts. It was historically important for the growth of the city, and was originally located in what is now the downtown area of the city. Land reclamation and conversion to other uses means that downtown area no longer handles commercial traffic, although the US Coast Guard maintains a major base there, and there is still considerable ferry and leisure usage.

Today the principal cargo handling facilities are located in the Boston neighborhoods of Charlestown, East Boston, and South Boston, and in the neighbouring city of Everett. In 2011, the port handled over 11.5 million metric tons of cargo, including 192,000 container TEUs. Other major forms of cargo processed at the port include petroleum, liquefied natural gas (LNG), automobiles, cement, gypsum, and salt.[50]

The Black Falcon Cruise Terminal situated in South Boston, was renovated and expanded in 2010. [51] During 2012, it served 117 ships and more than 380,000 passengers.[52]

Passenger boat services

[edit]

The MBTA Boat system comprises several ferry routes on Boston Harbor. One of these is an inner harbor service, linking the downtown waterfront with Boston Navy Yard in Charlestown. The other routes are commuter routes, linking downtown to Hingham, Hull and Quincy. Some commuter services connect via Logan International Airport. All services are operated by private sector companies under contract to the MBTA.

Outside the MBTA system, seasonal passenger ferry services operate to the Boston Harbor Islands, to the city of Salem north of Boston, and to the town of Provincetown on Cape Cod. Water taxis provide on-demand service from various points on the downtown waterfront and from Logan Airport, and in particular between the airport and downtown.

Several companies operate tourist oriented cruise boats on the harbor and on the Charles River. Other companies operate duck tours that use amphibious vehicles (mostly derived from World War II era DUKWs), and encompass both the city's streets and its waterways. On a much smaller scale, but perhaps more iconic of Boston, are the human-powered Swan Boats on the lake of the city's Public Garden.

Commuting statistics

[edit]The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Boston, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 83 min. 29% of public transit riders ride for more than two hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 15 minutes, while 24% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 7 km, while 12% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[53]

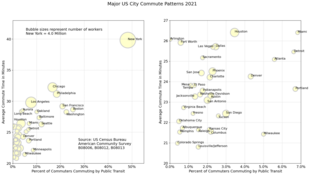

In 2013, the Boston-Cambridge-Newton metropolitan statistical area (Boston MSA) had the seventh-lowest percentage of workers who commuted by private automobile (75.6 percent), with 6.2 percent of area workers traveling via rail transit. During the period starting in 2006 and ending in 2013, the Boston MSA had the greatest percentage decline of workers commuting by automobile (3.3 percent) among MSAs with more than a half-million residents.[54]

In 2019, a yearly ranking of time wasted in traffic listed Boston area drivers lost approximately 164 hours a year in lost productivity due to the area's traffic congestion. This amounted to $2,300 a year per driver in costs.[55]

Aviation

[edit]

Boston's principal airport is Logan International Airport (BOS), situated in East Boston just across inner Boston Harbor from downtown Boston. Logan Airport is operated by the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) and has extensive domestic and international airline service. The airport is linked to downtown by several highway tunnels. The Silver Line bus rapid transit uses these tunnels to connect Logan's terminals with South Station. There are also shuttle buses between the terminals and the Blue Line Airport station.

To help address overcrowding at Logan Airport, Massport operates two other airports in eastern Massachusetts:

- L.G. Hanscom Field

- Worcester Regional Airport: formerly owned by the city of Worcester until ownership transfer to Massport was mandated by law in 2009,[56] and subsequently completed on June 22, 2010.[57]

In addition, MassPort has designated two out of state regional airports (which are administered independently) as reliever airports:[58]

- T. F. Green Airport near Providence, Rhode Island

- Manchester-Boston Regional Airport in Manchester, New Hampshire

There are also several general aviation facilities for private planes in the Boston area, including Beverly Regional Airport and Lawrence Municipal Airport to the north, Hanscom Field to the west, and Norwood Memorial Airport to the south.[59]

Since the September 11, 2001 attacks, strict security has been implemented at all of Boston's airports. Because of this and its location as the closest American port to Europe, Boston is an emergency destination for airliners that experience security or mechanical problems while en route to the US, although they may also be diverted to Halifax, Nova Scotia, or other Canadian airports.

Boston Vision Zero Plan

[edit]In 2015, mayor Marty Walsh announced that the city of Boston would become part of a worldwide program known as Vision Zero.[60] Vision Zero is a plan self described as “a new standard for safety on our streets.” The plan aims to eliminate deaths caused by transportation, whether that be pedestrians, personal vehicle riders, or cyclists.[61]

Since 2015, the city of Boston has adopted several different policies aimed to help bring down the number of fatalities caused by Transportation in Boston. These policies include the creation of a 25-mile per hour speed limit law citywide,[62] and the implementation of Neighborhood Slow Streets, a tool of Traffic calming designed to make personal vehicles slow down in residential areas.[63] Pedestrian deaths have fallen to 57 in 2019, down from the 2017 total of 82. Cyclist deaths have also fallen from 10 in 2017 to just 3 in 2019.[64]

Boston now seeks to expand this plan by committing more funds to the program, as they currently spend roughly five dollars per person annually on the Vision Zero plan, whereas cities like San Francisco spend upwards of seventy five dollars per person annually.[62] Boston aims to eliminate vehicle crash fatalities by 2030, while planning for more Neighborhood Slow Streets, speed humps, and curb extensions to help bring vehicle fatalities down to zero.[60] One area that the Boston Transportation Department specifically wants to focus on are the numerous Boston public schools, stating in their 2017/2018 vision zero report, that “We will be upgrading school zone flashers throughout the City and focusing on schools as we select locations for future safety improvements.” [60]

See also

[edit]- Greater Boston for a wider scope

- List of bridges in Boston

- List of U.S. cities with most pedestrian commuters

- MBTA accessibility

- Transportation in Massachusetts

- Free public transport in Boston

- Plug-in electric vehicles in Massachusetts § Boston

References

[edit]- ^ Katheleen Conti (September 17, 2015). " "Boston commute is as congested as it was 10 years ago". Boston Globe.

- ^ Walk Score. "About Boston". Walk Score. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "DCR web page".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 18, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Sherwood Stranieri (April 25, 2008). "Mixed-Mode Commuting in Boston". Using Bicycles. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- ^ MacLaughlin, Nina (2006). "Boston Can Be Bike City...If You Fix These Five Big Problems". The Phoenix – Bicycle Bible 2006. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011.

- ^ "Urban Treasures". bicycling.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2007.

- ^ "Urban Treasures". bicycling.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010.

- ^ Katie Zezima (August 9, 2009). "Boston Tries to Shed Longtime Reputation as Cyclists' Minefield". The New York Times. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ "A Future Best City: Boston". Rodale Inc. Archived from the original on February 11, 2010. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ "Boston gear up for influx of new bicycle riders". The Boston Globe. July 13, 2011. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ McGrory Brian (July 15, 2011). "Make Boston bicycle-free". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ "Drivers, bicyclists clash on road sharing". Turner Broadcasting System. October 18, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ Filipov, David (July 29, 2009). "Hub's bike routes beckon, white knuckles and all". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ "Urban Treasures". Bicycling Magazine. Archived from the original on July 7, 2007. Retrieved June 16, 2008.

- ^ "MassBike: The Massachusetts Bicycle Coalition". MassBike: The Massachusetts Bicycle Coalition. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ^ "LivableStreets: Rethinking Urban Transportation". LivableStreets Alliance. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ Metropolitan Area Planning Council. "Greater Boston Cycling & Walking Map". Metropolitan Area Planning Council. Archived from the original on March 4, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Rubel BikeMaps. "Welcome to Rubel BikeMaps". Rubel BikeMaps. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Association for Public Transportation (2003). Car-Free in Boston:a Guide for Locals and Visitors. Cambridge, MA: Rubel BikeMaps. pp. 192. ISBN 1-881559-76-9.

- ^ Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. "Schedules and Trip Planning Data (GTFS)". Rider Tools. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. "App Showcase". Rider Tools. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ^ http://www.seaporttma.org/pdf/Commuter%20Bus%20Services%20available%20to%20Commuters%202010.pdf [dead link]

- ^ "MassCommute - MassCommute - List of MA TMAs". masscommute.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ^ "Charles River TMA - Charles River TMA - Commuting Solutions". charlesrivertma.org.

- ^ "128 Business Council – Unlocking the Grid". 128bc.org.

- ^ "Shuttle Services - Partners HealthCare". partners.org.

- ^ "Routes". Archived from the original on May 6, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015. lists shuttles between LMA and Ruggles, JFK/UMass, Crosstown (near Melnea Cass Blvd.), M6/Chestnut Hill, Landmark Center, and Fenway

- ^ "M2 - Cambridge - Boston | MASCO". www.masco.org.

- ^ "Pop-up bus service Bridj to launch test runs June 2". BostonGlobe.com.

- ^ "Data-driven pop-up bus service to launch in Boston - Business - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com.

- ^ "Boston.com / Real estate". boston.com.

- ^ "Is parking too cheap?". boston.com.

- ^ "Parking Freezes - City of Boston". cityofboston.gov. Archived from the original on September 13, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2007.

- ^ EPA-Approved MA Regulations | State Implementation Plans (SIPs) | Topics | New England | US EPA

- ^ a b American Public Transportation Association. "Heavy Rail Transit Ridership Report 4th Quarter 2022" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 14, 2023.

- ^ "Fares Overview". Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ "Throwback Thursday: When the T Was Color-Coded". Boston Magazine. August 25, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ "MBTA: Mobile apps will be able to track Green Line trains by 2015". Boston.com. January 11, 2016.

- ^ http://www.mbta.com/about_the_mbta/news_events/?id=6442451214&month=1&year=14 MBTA press release on Keolis Commuter Services award

- ^ a b c d Comprehensive Railroad Atlas: New England & Maritime Canada. Steam Powered Publishing. 1999. ISBN 1-874745-12-9.

- ^ a b "Routes - Northeast". Amtrak. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ "Routes - Northeast - Downeaster". Amtrak. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ "Office of Governor Charlie Baker and Lt. Governor Karyn Polito". Mass.gov.

- ^ "Pan Am Railways and Norfolk Southern Create the Patriot Corridor to Improve Rail Service and Expand Capacity in New York and New England". Norfolk Southern Corp. May 15, 2008. Archived from the original on June 1, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ^ "Ethanol Safety Study". state.ma.us. Archived from the original on June 25, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ "Rail plan for ethanol is decried". Archived from the original on December 11, 2014.

- ^ Study of the Safety Impacts of Ethanol Transportation by Rail through Boston, Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Somerville, and Revere Archived June 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, MassDOT 2013

- ^ Trains Carrying Flammable Liquids Won’t Be Traveling Through Greater Boston Archived December 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Steve Annear, Boston Daily, July 3, 2013

- ^ "MASSPORT - About the Port - Port Stats". Massachusetts Port Authority. Archived from the original on April 9, 2013. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ^ "Black Falcon Terminal - Boston's cruise terminal". Boston Cruise Guide. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ "2013 Cruiseport Boston Fact Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ "Boston Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ McKenzie, Brian (August 2015). "Who Drives to Work? Commuting by Automobile in the United States: 2013" (PDF). American Survey Reports. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ "Boston Has Worst Traffic in Nation, According To New Rankings". WBZ-TV. February 12, 2019. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ Chapter 25 of the Acts of 2009. Archived October 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Section 148.

- ^ Massport (June 22, 2010). "Massport, Worcester Airport Deal Completed". Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MASSDOT). Archived from the original on June 26, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ^ "Regional Airports: FAQ". Massport. Archived from the original on February 21, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ "Airside Improvements Planning Project, Logan International Airport, Boston, Massachusetts" (PDF). Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration. August 2, 2002. p. 52. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c "2017/18 Vision Zero Boston Update" (PDF). Boston.gov. Boston Transportation Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ "What is Vision Zero?". Massachusetts Vision Zero Coalition. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "Boston". Massachusetts Vision Zero Coalition. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ "Neighborhood Slow Streets". Boston.gov. December 14, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ "Massachusetts Pedestrian and Bicyclist Fatalities Map". Massachusetts Vision Zero Coalition. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Boston Bikes - an official webpage of the City of Boston